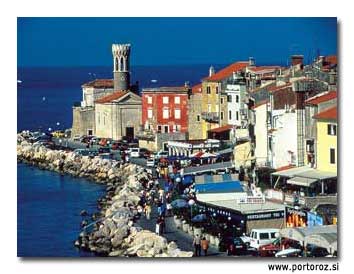

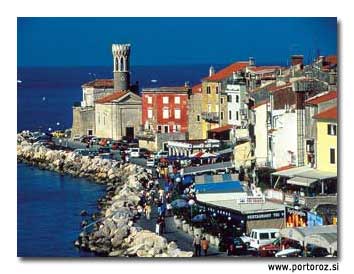

Sewn into the Šavrini hills and sprawling out onto a thumb-shaped promontory on the northwestern corner of Istria the largest peninsula in the Adriatic Sea, Piran represents the face of the Slovenian coast.

Mentioned in writings as early as the 7th century, Piran dons many monikers. Its climate and prime location on Slovenia’s 31-mile-long (50 km) coast have for centuries drawn European vacationers to the “gem” of the Venetian Gothic and the “Dubrovnik of the North Adriatic.” However, 16 years ago, Piran’s tourism declined during Slovenia’s War of Independence with Yugoslavia. Although the hostilities lasted only 10 days and did not affect Piran directly, travel to the country and region was deemed dangerous.

Today, tourism is prospering once again in this most-developed town in all of Slovenia.

Perched on a high hill and strengthened with flying buttresses, St. George’s Church is the centerpiece of this Mediterranean town. Construction probably began in the 12th century, but the church was built in its present size in the 14th century, and Baroque-style renovations were completed in 1637.

The medieval church is named after Piran’s patron saint. Inside, a museum showcases 14th century artifacts, murals from the Venetian painting school adorn the wall, and two statues of St. George are among the preserved works of art.

From the church’s courtyard, the sky extends to the Italian city of Trieste, about 35 miles (56 km) to the north, and the snow-capped Dolomites, with a view below of waves dashing onto the rocks on the stone beach.

St. George’s bell tower stands as a reminder of 16th-century Venetian rule. Built in 1608, the bell tower is a smaller-scale copy of the San Marco Campanile, in Venice. The bell chimes every quarter hour, serving as the town’s alarm clock. At the top of the tower, the brass angel St. Michael informs residents of incoming weather, pointing north for good or south for fair.

The cobblestone street east of St. George’s Church, up the steep hill, leads to the town walls. As early as the 7th century, walls surrounded Piran, and gates divided the town into districts. With the threat of a Turkish invasion in the 15th century; the walls were refortified, and a new wall was built on Mogoron Hill. The largest preserved section on the hill has crenellated towers, built for medieval defense.

The view from the walls offers a postcard shot of Piran, starting from the countryside below and reaching to the Punta lighthouse. West, toward the harbor, are the First and Second Rašpor gates, two of the seven remaining gates in Piran formerly used as entrances into the walled city.

Tartini Square, named for Piran’s most famous resident, classical composer and violinist Guiseppe Tartini (1692-1770) — and actually, in the form of a circle — is Piran’s social heart. The square, made of white marble, resembles an ice-skating rink, with a larger-than-life bronze statue erected to Tartini in the center.

Kids crowd the square playing soccer, women chat with friends, and tourists relax on benches while enjoying gelato. Town Hall, St. Peter’s Church and grand, multistory homes encircle Tartini Square.

Piran was part of the territory of the Republic of Venice, from 1283 to 1797. Venetian rule left a strong mark on the region, and Italian is still one of the two official languages spoken in Piran — the other being Slovenian, of course.

The 15th-century palace at the intersection of 9th Corps Street and Tartini Square called the Venetian House is the most beautiful example of Venetian Gothic architecture in Piran. Decorated with stone ornaments and a corner Gothic balcony, the red palace represents an infamous tale.

According to legend, a Venetian merchant fell in love with a local girl and built the palace for her. The merchant wanted the edifice to show his love and express the strength of his wealth to the townspeople, however, the townspeople disapproved of their relationship and gossiped about the couple.

As a defense against the town’s resentment, an inscription, still preserved today, was added between the windows on the second floor. It reads: Lassa pur diror “Let them talk.”

Inside the winding alleys the character of Piran reveals itself. The street signs remind visitors of the Yugoslavian communist past, with names referring to Russian dictator Vladimir Lenin and German socialist scientist and philosopher Friedrich Engels. Here and there, streets or staircases lead into dead ends or a view of the sea. The sounds of footsteps in this quiet place mix with the clacking of dishes and laughter echoing off the buildings. Residents smile as they walk down the street.

To the north, Piran’s alleys lead to the 1st of May Square, the old market and administrative center. The Old Square (Piazza Vecchia), as it was first named, is slightly elevated, with stairs leading up to statues of Law and Justice.

It bustles with locals — adults enjoy a glass of refošk, a popular red wine of Istria, at restaurants, and children play on the stone rainwater cistern, built as a reservoir after a drought in 1775. Two statues of babies flank the cistern, one holding a fish and the other a pot. The statues were connected to gutters that stored water in the cistern.

Where boulders protect Piran from the sea sits the Byzantine-influenced Punta Lighthouse. Reminiscent of the 7th century, when Piran was under Byzantine rule, the top of the lighthouse resembles a crown, and features Moorish keyhole windows with a cloverleaf at the top of each arch.

Some linguists believe the town’s name derived from the Greek word pyr, or fire, as the original settlement was positioned there to support a lighthouse for vessels sailing to a nearby Greek colony.

If You Go

Tourism Piran