Start the Journey At Early Morning

The huge, single-horned beast looks up and gazes at us in the early morning mist. Its thick, gray, leathery hide drapes down its flanks, like sections of armor plating.

Two small birds perch on its rump, pecking away at insects. The rhinoceros is unperturbed by the birds or our close approach, allowing us to observe it at leisure from high above.

My wife Annie and I are riding atop an elephant through the grasslands of remote Kaziranga National Park in the northeastern state of Assam, India, where most of these Asian one-horned rhinos are concentrated.

Several other elephants, each with a mahout (handler) and two or three visitors straddling a saddle, cluster nearby. Cameras click away. Soon, we encounter a small group of water buffalo. Grazing placidly, their broad, curving horns glisten with moisture.

Later, we pass a herd of nimble, swamp deer, dozens of them, which race away through the tall grass.

Safari in India

This safari, and others by jeep and on elephants, is the highlight of a visit to Assam, featuring an eight-day small-ship cruise along the broad Brahmaputra River, and includes two outings into the Kaziranga Park.

We then spend four more activity-filled days at a lodge within the national park itself. The park offers some of the world’s richest and most rewarding wildlife-viewing opportunities.

Unfortunately, a dark and sobering reality intrudes. Our jeep safaris are accompanied by uniformed park rangers, carrying powerful rifles, and these are for the protection of the rhinos, not the foreign visitors.

For years, gangs of well-organized poachers with AK-47s have been shooting rhinos and cutting off their horns.

These are smuggled out of India to be sold in Vietnam and China, where rhino horn is believed to have cancer-curing and other medicinal properties.

It is literally worth more per gram than gold, and the assault on the rhinos has recently surged. In 2012, 21 of these noble beasts were shot in Assam, but by mid-April of this year 17 more had already been killed.

The Baby Rhino

The situation made heart-wrenching international headlines when a 15-day old baby rhino was left orphaned by the death of its mother, whose corpse was not found until days after its killing.

The rhino calf, dehydrated and traumatized, needed special veterinary care.

In response, the government has beefed up its patrols of armed park rangers, supported by soldiers, and began training hundreds of additional rangers.

It has even deployed sophisticated, hand-launched observation drones to add extra eyes in the sky, because Kaziranga’s 185 square miles of rugged parkland is so difficult to patrol on a round-the-clock basis.

When armed poachers are caught within the park, the patrols do not hesitate; they shoot to kill, because the poachers fight back. In May, two forest guards were critically injured in a shootout with poachers.

Two poachers were shot and killed by rangers in March, and a handful of others arrested at their homes following investigations by India’s equivalent of the FBI.

Visiting A Simple House

Riding in a jeep to a distant area of the park, we stop to visit one of the outlying ranger posts, a simple house where small teams of men are stationed for weeks at a time.

Povi, our naturalist and guide, translates and explains the problems they face. The mighty Brahmaputra River discharges more water each year than the Mississippi.

When it floods in the monsoon season, as it does every summer, the roads in the park become impassable, and many of the rhinos are forced to seek higher ground.

When the rhinos spread out, they are especially vulnerable to poaching. Meanwhile, the rangers have to abandon their jeeps and patrol in small outboard-powered boats, which are slower and less efficient, hence the advantage of having drones in the sky.

Fortunately, the Indian and Assam governments seem quite aware of the importance of protecting the rhinos, and the need to commit whatever resources are necessary.

It is encouraging that, although the struggle against poaching is difficult, the rhino population has been gradually increasing. In 1910, there were only about 50 rhinos left in India.

A 2012 census counted 2,290 rhinos in Kaziranga alone, up from 1,672 in 1999. Today’s global population of one-horned rhinos is 3,300. (Most of the rest are in other Assam parks and in Nepal, where poaching has also been fierce.)

There is no danger to visitors like ourselves, so we feel free to enjoy our days of outings at Kaziranga.

Our Days at Lodge

Every evening, we return to the comfort and fine meals at our lodge, on a small river where animals come down to drink right opposite our thatched cottage.

We ride along the shores of swampy waterways on the back of an elephant, and see dozens of grazing rhinos.

We bounce along a jungle track in an open jeep and focus our binoculars and cameras on ospreys, eagles and storks. Agile, langur monkeys leap through vast banyan trees festooned with orchids, while mynah birds flit about.

A young water buffalo calf is nuzzled by its hulking mother. There are scratch marks on acacia trees, where Bengal tigers, seldom seen, have sharpened their claws.

We hike through a rubber plantation and a village of the local Karbi tribe in a forest full of green parakeets.

After each safari, the mahouts bathe and brush their elephants in the nearby river. The great pachyderms spray themselves and wallow in extravagant pleasure, a wonderful sight to behold.

If You Go

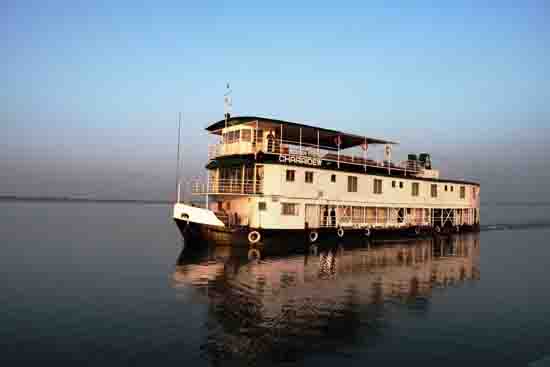

The 12-cabin Brahmaputra River cruise ship Charaidew and the 12-cottage Diphlu River Lodge are booked through World Luxury Cruises, www.wlcvacations.com, toll-free 877-579-7447.

Assam is remote but accessible by India’s efficient domestic airline system. Guests are met at airports by guides and modern SUVs.

A tropical medicine consultation is advisable, as are certain inoculations and malaria tablets.

Stomach ailments are unlikely if only bottled water is drunk and if meals are taken only on the cruise ship, or at the lodge, or at high-end hotels and restaurants in the major cities.

Author Bio: Tom Koppel is a veteran Canadian journalist, author and travel writer whose latest book, Mystery Islands: Discovering the Ancient Pacific, can be obtained by writing to [email protected].