“Life As Property – A Life With No Choices.”

Driving or cycling on historic Fort George Island Cultural State Park within the Timucuan Preserve in a very natural, expansive area near Jacksonville, Florida makes for a most pleasant day. Until you’re faced with some unpleasant history. Amidst the miles of a shaded lane that circles the island you’ll find walking trails, some homes, and even the charming, restored 1928 Ribault Club where events and weddings are held, and thoughtful kiosks present the wildlife and nature one can expect to find while kayaking the Fort George River or picnicking anywhere you like.

Just up from to the north from the club and around the bend you’ll find Kingsley Plantation, which at first glance seems like a perfect place to spread out a blanket and take in some sun or a view of the river. And it is, if you aren’t haunted by what took place on this parcel beginning in 1798.

The Enslaved People’s Story

“That is the “Witness Tree,’” said Felicia Boyd, a naturalist with the Timucuan Parks Foundation, who showed me around the island and the property, which is a National Park Service Site in the Timucuan Ecological Historic Preserve.

The Witness Tree is old enough to have stood there when this site was a plantation.

“The ‘Witness Tree’ is very old, so it is said to have witnessed the lives and deaths of the enslaved people. There are areas near it where graves have been found.”

As I stood in the sunshine on a mild April day, I felt my blood run cold.

“This was a working plantation. They picked Sea Island long-fiber cotton, which was very valuable. As you can see it’s on the Fort George River so they could pick the cotton and put it on the ships and send it off to Europe,” Boyd explained.

Just then I saw a bass boat with sport fishermen speed south along the shore.

A Typical Yet Unimaginable Day

Historic records indicate the enslaved people were on a “task system.”

A task system meant those who were enslaved, worked without supervision because Fort George Island was isolated and only reachable by boat, would have to do a certain amount of work and then they could work on their own gardens and spend time with their families. A small, sample garden grows on display.

“It was a very difficult life,” said Boyd as we stood between the kitchen house and the main plantation house in front of one of the informational kiosks which indicated 16-hour workdays during harvesting season in oppressive heat and mosquito-filled humidity. I was struck by the irony of seeing a covered breezeway between the two buildings to provide shelter and comfort while the enslaved were toiling steps away in the blazing sun or driving rain.

The white plantation house, which looks over the river on one side and the ruins of 23 tabby slave cabins in a semi-circle on the other, was constructed by enslaved people in 1798. It’s the oldest remaining plantation house in Florida. The tabby cabins walls were thick – made with a mixture of oyster shells, sand, and water.

“The cabins were not large, and they were very primitive,” said Boyd. “Usually when you come to a plantation the focus is on the planters house and the plantation family. But the large majority of the people who lived on the plantation, 60 at Kingsley, were the enslaved.”

Facing the Truth

Boyd said that maintaining the 60-acre plantation and providing access to visitors gives the National Park Service and Timucuan Parks Foundation the opportunity to tell the story of the enslaved people who lived there.

“When you’re at the plantation you can walk through the grounds or take an audio tour, or you can just read the panels. You can experience what it must have been like 300 years ago.”

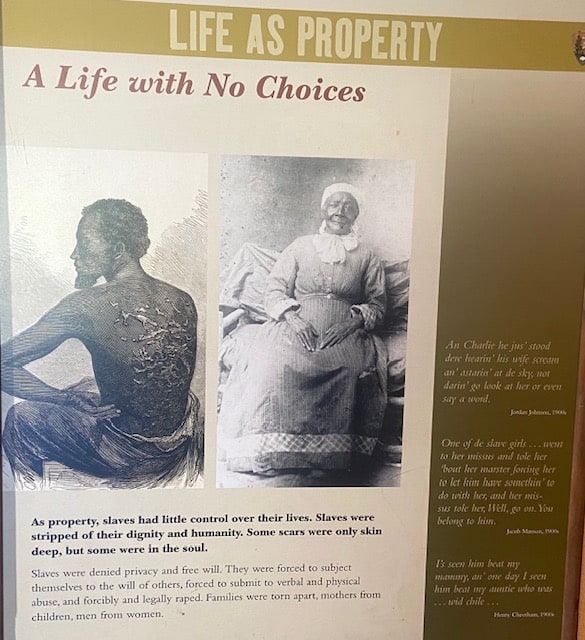

The audio tour is told dramatically, and the panels are not light reading. Inside the barn a panel was titled: “Life as Property – A Life with No Choices.” The panel detailed how enslaved people were stripped of their dignity and humanity and how some scars were only skin deep, but some were in the soul.

“They were forced to submit to verbal and physical abuse and forcibly and legally raped,” the panel read.

Bride and Prejudice

Zephaniah Kingsley settled at the plantation with his wife Anna, an enslaved women from Senegal he’d purchased in Cuba. She actively participated in plantation management and went on to purchase her own enslaved people and land. She and their four children eventually moved to Haiti where Kingsley, decrying a spirit of intolerance and prejudice in Florida and seeking more humane treatment for his 200 enslaved people, established a colony for his family and some of the people he enslaved, according to park service literature.

Nevertheless, it was, for me, a powerful visit to Kingsley Plantation. The preservation of the building made it easy, but unsettling, to walk the grounds and visualize what daily life was like on the very spot in which I stood. This was no movie set, though. This was real life. And the dichotomy of something unimaginably ugly happening in such a naturally beautiful and peaceful setting wasn’t adding up.

Boyd suggested to me that the now quiet tranquility of the Kingsley Plantation property offered an opportunity for peaceful reflection on the history of humanity.

Read more of Michael Patrick’s work at The Travel Tattler, or contact him at [email protected]