Standing near a bank of mechanical typewriters across from a row of Teletype machines, I marveled at the underground lair I was exploring. Hundreds of meters below the surface of the little town of Konjic in Bosnia and Herzegovina, sitting unused, is Tito’s bunker. An underground bomb shelter that took 26 years to complete (from 1953 to 1979), Tito’s bunker is something out of an early James Bond film – and it’s a fascinating day adventure if you are visiting the Balkans.

I was living and working in Sarajevo when my office offered a guided group tour of this hidden structure. I jumped at the chance to see behind the curtain. Josip Broz Tito, the Communist president of the former Yugoslavia, from 1953 to 1980, was quite paranoid about a Soviet invasion or nuclear warfare and this shelter was created to assuage his fears. Roughly an hour outside of Sarajevo, the bunker is said to be the very embodiment of the cult of personality surrounding Tito.

I wasn’t sure what to expect. We headed out at the crack of dawn for the start of the tour. Adjacent to the picturesque Nertva River, the bunker is hidden from view. The group and I entered a rambling vacation home, passing just one guard at the door. Through to the attractive entrance hall with its wooden shoe caddy and antique coat rack, we began walking down a long, cold, gray cement hallway, until we reached a second hallway and a big steel door. We were greeted by a Kalashnikov-toting soldier, who explained the general history and facts about the place. Then he spun the giant wheel lock (like a bank vault) and we were inside Tito’s bunker. Dark, damp and cold, I expected Dr. Evil to come sauntering down the hall at any time. As if being warped into the past, everything felt as if one was back in 1967, from the apparatuses and stark décor to the general idea of a bunker.

The bunker was built in a simple u-shape, with one long cement white painted tunnel serving as the main hallway, very sterile and expressionless. At evenly spaced intervals hung white florescent lights, which gave me the feeling of being in a hospital or prison. Each room off this hallway was done in mustard browns, muted reds and drab olive greens or remained in standard white. There was nothing to provide any sense of comfort or human touch, a reminder that this was built to be a war command post.

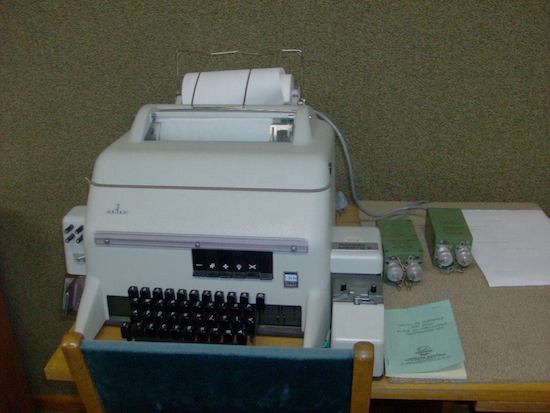

It was designed to house all the members of parliament (approximately 350 people). There is a large cafeteria, tons of small bedrooms with bunk beds and multiple workrooms. Entering into one office space with plain gray nylon carpet, I was amazed at the historic equipment – adding machines, an overhead projector and spindles of paper to be attached to the typewriters. Everything was still in pristine condition, ready for use in a crisis. Conspicuously absent were computers or anything that even remotely looked like a laser printer.

Moving from the office spaces to conference rooms, we were greeted in each chamber with one giant size framed picture of President Tito himself, looking dapper in his green and red Communist dress uniform, complete with aviator sunglasses. It was a notice, I suppose, for those stuck in the bunker of why they were down there and who remained their boss.

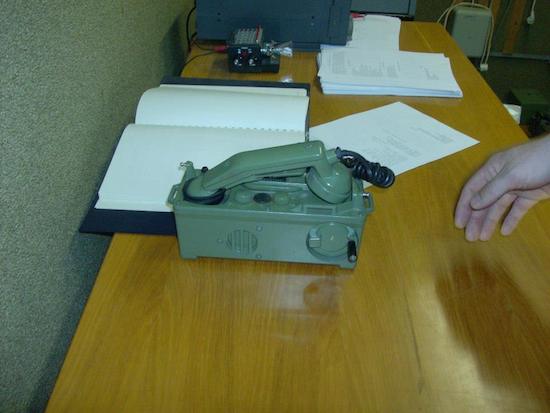

Aside from the usual table and chairs, the conference areas had two to three rotary dial telephones, one always in red (for disasters) and a 1950’s style microphone. Yet, what caught my eyes the most were the large world maps. Created in the 1970’s, these maps were in nearly all conference spaces and reflected a world order that no longer exists. In bold, dominating half the page, was the U.S.S.R. and a glance at Africa showed names of countries that no longer exist. They were artifacts from a time gone by, laid out for all the visitors to see and touch, but no longer relevant.

After seeing the main rooms, including climbing a ladder to catch a peek at the huge tanker of fresh water reserves and the large electrical generator cabinets (which still power the entire bunker today), we were lead to the highlight of the tour, Tito’s personal rooms. Coming to a wide gallery off the main hallway, we moved past more framed pictures of Tito and some art work before ascending a tiny set of stairs, to a small alcove, the place where those who wanted an audience with Tito would have bid their time.

To the left of this makeshift waiting room was a carpeted hallway with roughly six or seven bedrooms, with double beds, as well as three or four offices with the standard issued typewriter and rotary telephone of the day. These quarters, we were told, were for those in Tito’s inner circle. Not overly spacious, they were definitely two to three feet bigger then what we had seen in the general space and came with better furniture. To the right of the waiting area were Tito’s personal chambers.

Thinking I would see a lavish apartment with luxury trappings, I was surprised to find four simple small separate rooms: Tito’s office, his bedroom, a sitting area. The last in the compartment was a dressing room for Tito’s wife, Jovanka Broz. This was the one spot in the entire place with any sense of character. Someone had decided to give the walls pink and green wallpaper. There was a vanity where she could sit comfortably and apply make-up. Plastic still covered the furniture.

Throughout the tour, I was a little afraid of getting lost. The dwelling is quite cavernous and since it’s built into the side of a mountain, you couldn’t text or phone your way out. The bunker, also known as the Atomic War Command, was never occupied. Finished in 1979, Tito died in 1980 and thankfully, the former country of Yugoslavia was never involved in any nuclear wars. Tito’s bunker only became known to the general public after the 1990’s Bosnian war.

Leaving the bunker, happy to get above ground and see the sun, I couldn’t help but think Tito’s bunker was a fantastic flashback to the Cold-War era of cloaks and daggers, remnants of which are disappearing around the world.

For a glimpse into secrecy, espionage and mystery, a tour of Tito’s bunker is not to be missed.

If You Go:

The bunker is not open for the general public; to visit you must make arrangements through a local Bosnian tour company.

Organizations that will take you to Tito’s bunker:

Trip 2 Bosnia & Herzegovina

https://www.trip2bosnia.com/tours/tour-of-titos-bunker/

Insider City Tours & Excursions

https://www.sarajevoinsider.com/

Sarajevo Funky Tours

https://www.sarajevofunkytours.com/