It’s nearly 7:00 am. A rooster is screeching in the taro patch beneath my bedroom window as the sun begins its ascent. In the far distance, another rooster screams in reply.

Back and forth they go in call and response like two preachers urging their flocks on. Unimpressed hens cluck and scratch nearby.

A state-side friend, the granddaughter of an Orthodox Jewish poultry merchant, facetiously suggested I put out corn kernels dipped in instant glue to stop the roosters’ screaming. If there were corn kernels to be had on this remote Pacific island, it’s a tempting idea at times.

Where is Yap?

I live in Colonia, the only town on a 38½ square mile island called Yap, just 9 degrees north of the equator in the northwestern Pacific Ocean.

The 607 islands and atolls that make up Yap’s independent mother country, the Federated States of Micronesia, are scattered like pearls tossed from the hand of the ocean goddess Amphitrite across 1 million square miles of open water.

Four of the 65 inhabited islands serve as the country’s states. Yap is one of them. Dubbed “The Land of Stone Money” by the island’s tourist bureau in honor of the traditional form of currency, Yap is also reputed to have one of the most intact ancient cultures in the entire region.

Stretching 600 miles east of Yap’s main island are 78 outer islands and atolls, of which only 18 are inhabited. As the government and commercial center, Colonia is a crossroads set midpoint between the north and south ends of these four contiguous islands that make up the mainland.

In this ancient clan culture, whether you are from the north or the south is an important marker that remains with you from birth to death. Not unlike the island that I’m from – New York City’s Manhattan island — that has its own north-south dividing point.

Life on Remote Island in the Pacific

With no animals on this patch of volcanic rock and clay, other than feral dogs and cats and penned pigs that are given cracked coconuts to grow fat on, corn kernels would need to be ordered from Amazon.

And that would mean waiting for several weeks, or even months, while the package wends its way across the Pacific Ocean on a container ship from southern California with stops at islands between there and Guam, where the packages are transferred to Yap’s twice-weekly United flight.

COVID-Free

However, that was before the pandemic slammed into the world and all travel was banned by the national government. Currently, there are only 10 countries in the world that are covid-free. All are Pacific Island nations.

The mail now comes in from Guam every Thursday on an Asia Pacific Air flight contracted to pick up the commercial fish haul and large plastic bins of pre-packaged betel nut for export to regional markets. Supply ships also arrive intermittently during the month laden with food, cars, construction materials, and other supplies.

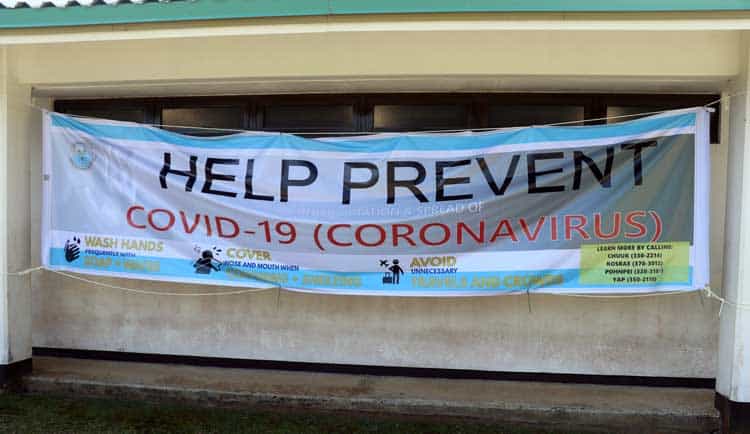

Strict Safety Protocols

Strict protocols are in place to prevent COVID from hitchhiking in. The crews are not allowed to have contact with the local workers and all incoming mail and cargo is quarantined for four days and sanitized at the airport and dock before it can be opened.

Only then will a frayed, yellow card announcing the arrival of a package be put in my mailbox at the one US Post Office that serves the entire state and its 11,000 residents. The post office is bustling every Tuesday afternoon when the mail is released from its confinement.

United is now flying in once a month or so to take passengers who are allowed to leave to Guam. Non-citizens of FSM, patients in need of care not available at Yap’s small hospital, and students going back to school fill a few of the seats.

Travel Ban

All other FSM citizens that don’t meet that criteria are required to stay put. And once off the island, no one is allowed to come back in until the travel ban is lifted. It’s unknown when that might be.

As a US citizen, I could leave, but why tempt fate someplace else while Yap is still safe.

FSM issued an emergency declaration on January 31 that banned entry by anyone coming from China or another infected location. The declaration was renewed and the door was finally shut to everyone in late March when the last 145 passengers arrived in Yap from Guam and Palau.

Quarantine

They were immediately quarantined for nearly one month upon arrival, the first two weeks spent at two hastily furnished and prepared schools and in the gymnasium of the sports complex depending on their arrival date. For the other two weeks, they were directed to stay at home in self-quarantine.

When sent home, several of the passengers ignored the mandate and were reported to be wandering around the community. Swabs were taken from them and sent to Guam, the nearest location with test kits by then.

They were told to stay home and a temporary nighttime curfew was put in place, basic handwashing stations set around the island, and social distancing advised in an attempt to prevent the spread of the virus in case they exhibited symptoms or tested positive. Three of them experienced COVID-like signs during their confinement and were immediately isolated in the hospital’s ICU.

Everyone breathed a sigh of relief when the tests came back negative, but the concern was still high among the doctors and nurses when it was reported by the CDC that the tests were not 100%.

Once cleared, the patients were released and sent home to finish their mandated quarantine. Since then, the island’s Health Crisis Task Force has received test kits for on-site testing.

Changes on Yap

Even with no daily fear of contracting the virus, life has been disrupted much as it has been in other parts of the world. With the travel ban and the arrival of the last group of passengers came the shutdown of the handful of small, family-owned hotels and dive resorts.

Most of their employees were sent home. Government offices and schools shut down for several weeks. Residents were – and still remain – stranded in Guam, Hawaii and Oregon, among other locations. Students attending college in Guam, Hawaii and the mainland US had to find places to stay when their schools closed.

The FSM Congress announced financial aid for those who were unemployed and provided some assistance to those who were unable to return from overseas. But it took several months to set up the program and manage the application process.

Most families have small gardens and everyone has a taro patch. Taro does not require cultivation until needed, providing food security along with the staples of bananas and coconuts.

The FSM Congress announced this past week that they are working on a solution to repatriate those who have been unable to return home.

But many who remain in Yap, including the state’s Health Crisis Task Force, do not want to open the border until a cure or vaccine is available. They warn that the virus will race through the small population of only 7,000 inhabitants once it arrives.

Among the equipment and supplies that have been ordered are dozens of body bags. The small mortuary next to the hospital will be overwhelmed. Bodies will need to be rotated in and out of cooling units due to its limited capacity.

Health Crisis Task Force

The Health Crisis Task Force was already working together to combat an outbreak of dengue fever beginning in late 2018. Now their attention has turned to COVID-19 with an increased number of people from the non-profit and public sectors serving on the committee.

A command center was established at the small hospital and twice-daily meetings begun. Subcommittees were formed to address everything from where to establish a quarantine and isolation site and how to educate the public on this new health threat, to developing protocols for the unexpected arrival of fishing and pleasure boats, the arrival and immediate burial of human remains that might be contaminated at an off-island mortuary, and the possibility that an airplane might be grounded and the crew required to be housed safely away from airport personnel.

Just last week a commercial fishing boat went aground on the reef late at night. They have been fishing in closed FSM waters for several months, long enough that it’s doubtful they have COVID.

But precautions were taken and the crew of nine transferred to their life raft and were towed to shore where they were isolated in temporary tents, provided food and water, and met with trained nurses wearing masks, face shields, gloves, gowns and other protective gear to administer the test.

A team was sent out to the boat by the Yap Fishing Authority to unload the fuel and take care of other emergency environmental procedures.

The small staff of doctors, nurses, lab technicians and support staff are doing their jobs as usual, but they were swiftly caught up in the planning, preparation and training needed to respond to the virus when it arrives.

Communal Living

One hazard is the common practice of communal living in these islands. Extended families live together with mothers, fathers, children, grandparents, aunts and uncles from newborns to elders interacting daily.

A group of trained COVID educators fanned out and visited every home to hand out brochures and help identify areas where family members could be isolated if and when necessary. They also visited every business on the island to assess readiness against certain criteria.

I got a knock on my door one Saturday morning from the woman assigned to my village. She handed me a brochure explaining preventative measures, the signs of infection and what to do if I experience any of them.

She then filled in a form with my name and contact information and asked a few questions, before moving on to my neighbors: Where do you get your water from? Is it filtered? Do you have somewhere to isolate yourself? How many people live with you? Where do you work?

No Restrictions

With no COVID on the island, I am not confined to my apartment like my friends in the U.S. and Australia. The government offices are open again and schools are back in session. The hotels remain closed, but the few restaurants and all of the shops are open.

I am free to move around, go to the laundromat, meet friends for lunch, attend business meetings, and visit the stores to see what’s come in on the most recent supply ship.

I also meet with two Russian friends twice a week to help them increase their English language skills. Last night they invited me to have grilled lobster at their home outside of town, and tomorrow we’re going to motor out to the reef on their small boat.

The stores have spray bottles of alcohol hanging on the outside of their doors; the banks and post office have put down orange tape on their floors to indicate the six feet of distance required when standing in line; we’re told to practice social distancing, which the national government mandated recently, but no one adheres to it; and we still shake hands. That will change when the travel ban is lifted.

What is the New Normal?

In normal times now past, visitors arrived from the United States, Canada, Germany and other points on the map to experience this rarified place and dive with the manta rays.

Now we wait for the new normal to arrive, a normal that no one can predict or fully comprehend.

It’s not tropical heat that has kept the virus at bay. It’s a rock-solid, no-one-allowed-in travel ban and a health crisis task force that’s been working around the clock for the last seven months to make sure nothing breaches the reef that surrounds this island that sits near the edge of the Yap Trench, a branch of the more famously deep Marianas Trench.

Despite the preparation, it’s agreed that it’s not a matter of “if” but “when” the virus arrives. Most agree it’s best to keep the gate closed as long as possible despite the challenges. So we wait and watch for what will happen next. But for now, we are safe.

I am in my fifth year of living in this green forest of cultivated taro patches and palm, coconut, mango, lemon, mahogany and breadfruit trees surrounded by a natural ocean aquarium filled with manta rays, reef sharks, sea turtles, octopuses, and thousands of brightly colored reef fish, anemones and coral.

At night, land crabs scuttle across the road under the light of the moon while fruit bats whoosh overhead searching for insects.

During the day, the sun beats down, waves are heard in the distance crashing against the fringing reef beyond the harbor, and the strutting roosters continue to compete for dominance beneath my window while a small, green gecko perches motionlessly above the window waiting for a tasty fly to come by.

Read More About Yap:

T-Shirt Economy on Yap

MantaFest on Yap

Festival on Yap

Author Bio: Joyce McClure is a freelance writer and photographer who moved to the remote island of Yap in the western Pacific Ocean in August 2016 as a Peace Corps Response Volunteer after a long career in public relations. At the end of her service, she decided to remain in Yap to continue writing and working with community organizations.

- Travel Guide to Greece - April 16, 2024

- A Portugal Getaway: Four Days in Lisbon and Sintra - April 16, 2024

- Love the Lava: Reynisfjara, Iceland’s Most (In)Famous Black-Sand Beach - April 16, 2024

Fascinating piece! I really enjoyed reading about her life and am inspired to head to the tropics as soon as I can!