Go World Travel is reader-supported and may earn a commission from purchases made through links in this piece.

Tell anyone you’re going on holiday to Uzbekistan and the reaction is unlikely to be warm and fuzzy. Blank stares were the most common reaction I encountered in the days leading up to my departure.

It also didn’t help my state of mind to read accounts of tourists fallen foul of Uzbek authorities’ aversion to certain prescription medicines.

Why You Should Visit Uzbekistan and the Silk Road

But I was in for a surprise. Uzbekistan is opening to the world at a remarkable pace and warmth and hospitality were the order of the day everywhere I went. With a growing list of countries whose citizens can visit with minimal visa fuss, independent travel has never been easier.

Yet there is almost none of the cynicism and hassle that one sometimes encounters at more established tourist destinations.

One of Uzbekistan’s defining characteristics is its location astride the Silk Road, a series of ancient trade networks linking China with Europe and East Africa.

The merchants’ caravans brought wealth and power to the urban centres along their route. But the cultural connections they fostered contributed to the emergence in the region of seats of learning and artistic endeavour. These rivalled, and even surpassed, the great cities of Europe in the Middle Ages.

Stunning Samarkand

Today, this legacy lives on in the richly textured domes, soaring portals and tapered minarets of Samarkand, Bukhara and Khiva. About two hours by high-speed train from the capital Tashkent, Samarkand is bound to impress and delight in equal measure.

Registan Square, surrounded on three sides by centuries-old madrassas (Islamic schools), is the first port of call for most visitors to the city. However, opportunities for memorable exploration are everywhere. The imposing tombs of Shah-i-Zinda, tiled in blue and turquoise and thronged with pilgrims, are a magical place to visit at any time.

Furthermore, the broad avenues and ornate facades of Samarkand’s Russian Quarter are more reminiscent of a European city than anything one might expect to find in Central Asia.

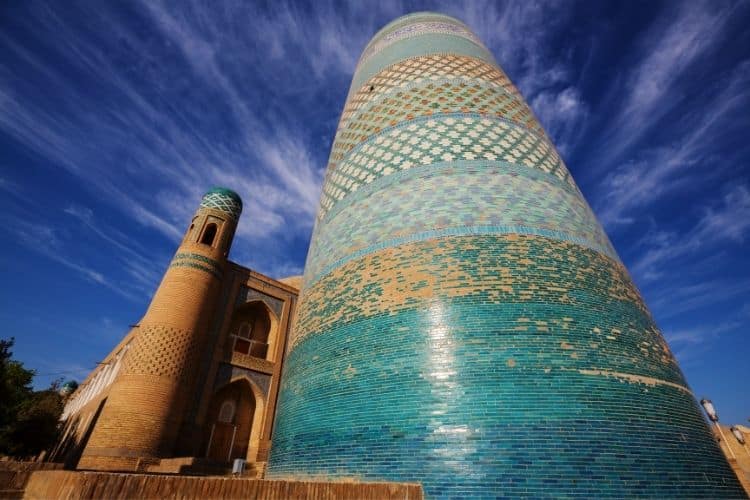

Kalta Minor Minaret in Khiva

Travelling west to Khiva, long notorious as a centre of the Central Asian slave trade, it is easy to imagine the wonderment of visitors to the city in centuries past. Completely surrounded by distinctively sloping walls, Khiva is a car-free warren of narrow winding streets, punctuated by mosques, madrassas and the occasional museum that was once a merchant’s stately mansion.

The city is also home to the Kalta Minor Minaret, which must rank as of one of Central Asia’s most iconic landmarks. Sitting squatly on Khiva’s main thoroughfare and covered entirely in brilliant blue tiles, the minaret was to be the highest in the world when it was commissioned by Mohammed Amin Khan in 1851.

However, the Khan was assassinated before it could be completed, and his more frugal successor immediately called off the project, leaving the minaret in its perpetually unfinished state.

Western Uzbekistan

In many ways, western Uzbekistan is a land apart from the rest of the country. It is remote and sparsely populated. However, the region’s unique character is underscored by the fact that a large swathe of it has been designated the Republic of Karakalpakstan.

It is technically autonomous but in practice, it’s one of the poorest parts of the country. Yet the people here are welcoming and the opportunities for exploration and adventure are nearly endless.

The Kyzylkum Desert dominates Karakalpakstan’s landscape. Meaning “red sand” in the local Turkic language, Kyzylkum’s red-tinged dunes provide an ideal backdrop for camel treks or overnighting at a yurt camp under brilliantly starry skies.

Fortresses & the Aral Sea

The region is also dotted with the remains of dozens of fortresses, some more than 2,000 years old. They once guarded the frontiers of an ancient empire against nomadic incursions from the north. Easily accessible on a day trip from nearby Urgench or Khiva, these fortresses are in varying states of decay. Yet they are still a joy to explore with often superb views from atop their crumbling ramparts.

Visitors are also drawn to western Uzbekistan for the chance to see firsthand the remains of the Aral Sea, once the world’s fourth-largest lake. Previously home to a diverse ecosystem and thriving fishing economy, the sea came close to disappearing entirely in the last decade of the 20th century.

With Soviet central planners focussed on boosting cotton production in Central Asia, the rivers feeding the Aral Sea were diverted for irrigation purposes beginning in the 1960s. Unsurprisingly, the results were a desiccated landscape and the loss of a way of life for the communities dotting the Aral Sea’s (former) shores.

While rehabilitation efforts have yielded some positive results, the remains of fishing boats rusting away in the desert near Moynaq serve as an enduring monument to environmental mismanagement on a colossal scale. Moynaq is also the starting point for many Aral Sea excursions.

The Savitsky Museum in Nukus

An entirely different sort of monument awaits those who make it to Nukus, western Uzbekistan’s largest city and main transportation hub. It is often vilified for its decaying Soviet-era architecture and past association with chemical weapons testing. Nonetheless, Nukus is home to one of the most remarkable art museums anywhere in the world.

The brainchild of maverick Russian archaeologist Igor Savitsky, the museum was founded in the mid-1960s. It then became a haven for the work of avant-garde Russian painters banned elsewhere in the Soviet Union.

Largely cut off from the outside world until Uzbekistan gained independence in 1991, the Savitsky Museum is a treasure trove of both ancient and modern art. It is justifiably finding its way onto more and more travellers’ bucket lists.

Tashkent: Capital of Uzbekistan

For many visitors to Uzbekistan, the capital Tashkent is merely a stopover between the international airport and the lowland Silk Road cities. This is a pity, as Tashkent has much on offer to those who linger.

Although the city was badly damaged in an earthquake in 1966, leaving upwards of a quarter of the population homeless, subsequent reconstruction efforts have left a fascinating melding of old and new.

Nowhere is this fusion more evident than at Chorsu Bazaar in the heart of Old Tashkent. Combining classic Soviet modernist design with the patterns and colours of traditional Central Asian architecture, Chorsu is an unmissable landmark. It is also a great place to hone your bargaining skills.

Casting back to an earlier era in Tashkent’s history, nearby Kukeldash Madrassa seems a world away from the rapidly modernizing city that surrounds it. Dating to the late 16th century, the madrassa’s flower-filled inner courtyard provides a peaceful setting for those who study or visit here. A scene that belies the building’s tumultuous history.

It resumed its original function as a religious school in the 1990s. Prior to that, Kukeldash had served variously as a travellers’ inn, a fortress and, during the Soviet period, a museum of atheism

Western Tian Shan Mountain Range & Fergana Valley

North-east of Tashkent, the landscape becomes increasingly rugged as the road edges its way into the Western Tian Shan Mountain range. Home to Ugam-Chatkal National Park, the region’s snow-capped peaks and steep valleys offer all manner of outdoor pursuits. Within easy reach of the capital, there is hiking and white-water rafting in the summer and surprisingly good skiing during the winter months.

Meanwhile, an upgraded highway follows the mountain range’s southern fringes along a traditional Silk Road route. It goes through the Kamchik Pass and into the Fergana Valley beyond.

An enormous bowl where the borders of Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan meet in a confused jigsaw, the Fergana Valley’s rich soil has supported settled agriculture for thousands of years. Today it is Uzbekistan’s breadbasket as well as its most densely populated region.

Ruled by a succession of empires since Alexander the Great swept through Central Asia almost 2,500 years ago, the valley’s tumultuous history continued in the post-Soviet period. Then, local activism was met with harsh repression, most notoriously in 2005 when troops fired on protesters in the town of Andijan, killing hundreds.

While the Andijan massacre remains a sensitive topic in Uzbekistan, security measures are now much relaxed. Visitors will find it just as easy to travel here as they would in any other part of the country. Except there are fewer tourists and local people are especially hospitable.

Kokand on the Silk Road

Most trips into the Fergana Valley begin in Kokand, and with good reason. It was once the capital of a kingdom with three million subjects and a territory larger than France. It was then unceremoniously annexed into the Russian Empire in the late 19th century.

Kokand today is a pleasant yet unassuming place with a remarkable landmark in the centre of town. The legacy of the kingdom’s last ruler and completed in the final years of his reign, the Palace of Khudayar Khan is an orientalist’s dream.

Built by an army of labourers overseen by master artisans, the Palace is studded with small courtyards. Each one is surrounded by exquisitely decorated rooms that seamlessly blend Central Asian and European styles. It displays what must have been a potent if short-lived projection of the Khan’s wealth and power.

The Fergana Valley lacks a Silk Road city on the scale of Bukhara or Samarkand. However, it has achieved enduring fame as one of the main sources of the fabric that gave its name to the caravan routes across Asia.

Fine silks were already being produced here at the time of the Arab conquest in the 8th century. Traditional techniques continue to be used to this day. The same holds true for other crafts historically associated with the Fergana Valley. This includes the embroidered skullcaps and distinctly shaped knives of Chust and the ornately patterned ceramics of Rishtan.

Tourism in Uzbekistan

For many visitors, seeing an accomplished artisan at work and having the chance to bring home one of their creations is a fitting bookend to a trip to Uzbekistan’s Silk Road.

In 2016 the country first embarked on a program to reform and energize its tourism sector. Since then, the number of international visitors to Uzbekistan has grown exponentially, reaching close to 7 million in 2019.

While the COVID-19 pandemic has put a brake on this upward trajectory, there is no doubt that growth will resume as travel restrictions ease. With the prospect of larger crowds in the years ahead and so much to see and explore, what better time than now to start planning a post-pandemic trip to Uzbekistan?

Book This Trip

Start planning your adventure to Uzbekistan today. Get prepared with more information on hotels or VRBO options, local restaurant recommendations, and more interesting sights to see through TripAdvisor and Travelocity.

- What It’s Like to Live as an Expat: Lake Chapala, Mexico - April 18, 2024

- Top 5 Spots for Stargazing in North Carolina - April 17, 2024

- The Low-Key Magic of Ghent, Belgium - April 17, 2024