Many historic tourist attractions are re-creations of lost events from the past, and are, at best, someone’s idea of how things used to be and, at worst, a caricature of how someone would like it to have been.

The USS Battleship Alabama, at Mobile, is neither. It is a real and tangible link with the past. Virtually unchanged since 1945, you can almost hear the echoes of past inhabitants and sense the life that coursed through the ship.

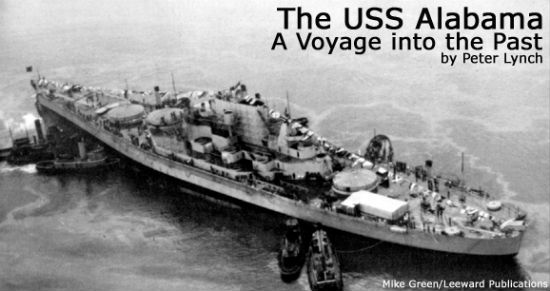

We can see the USS Alabama long before reaching it, just sitting there looking vast and formidable. There’s no hype, no phony sailor guides, no modern sponsorship, no games. It’s World War II incarnate.

Although dwarfed by today’s aircraft carriers, at 680 feet (207 m) long, 108 feet (33 m) wide and weighing 42,500 tons fully loaded, it was formidable in its day.

Walking up the gangplank, the intimidating bulk puts you in your place. It’s not a boat, but a floating town and it still looks ready for business. Climbing down the metal steps into the bowels of the ship is an eerie experience, each footstep echoing through the deserted ship.

Every deck tells a different story, empty room after empty cabin after empty workshop with each one a reminder of the men who lived and served there.

Shipboard life is evident everywhere — huge kitchens with fold away tables and chairs, even a soda fountain that was said to serve up to 100 gallons (379 l) of ice cream a day. No space is wasted on a warship. Dining rooms double as recreation and meeting rooms and the sleeping quarters house dozens of canvas bunks hanging by chains from the ceiling, three and four high, row after row.

Home to nearly 2,500 men, the USS Alabama was as large as the hometowns many of its crew came from. In fact, it was run like a small town with a chief of police (chief master of arms), a church with minister, a post office, a fire station, a hospital, a dentist and a prison (the brig). All the essential facilities are there — workshops, carpenters, laundry, cobblers, butchers, bakers.

It had everything necessary for feeding, servicing and maintaining a small town.

The technology of more than half a century ago seems cumbersome by today’s standards, but the battleship’s mechanical complexity and formidable firepower is still impressive. The Alabama saw active service in the North Sea assisting the British Fleet escorting convoys to Russia and extensively throughout the Pacific, eventually steaming into Tokyo Bay in July 1945.

While sitting in the dining area another visitor told me his grandfather served on the Alabama during WWII. “He never would talk much about what he saw and experienced. I think it was just too painful. I am so thankful that the USS Alabama has been preserved; it has allowed us a glimpse of part of his life that none of us knew anything about.”

Other relics of World War II can be found in Battleship Memorial Park, including the submarine USS Drum and many fighter planes. Key military vehicles and equipment from the Korean, Vietnam and Cold wars are on display, and there are interactive activities for kids in the air-conditioned museum. A snack bar and gift shop are also on site.

However, the USS Alabama is the star. It is truly a ghost ship, exactly as it was in 1945, except everyone has gone. It is not simply a tourist attraction, but a magnificent memorial that respects and evokes the presence of the people who served on it. The USS Alabama is not just another must-see attraction. It is an absolute must-experience event.

If You Go

The USS Alabama is at the Memorial Park, 2703 Battleship Parkway, Mobile, Ala., Hwy 90/98 off I-10 Exits 27 or 30. It is open from 8 a.m. daily and the entrance fee is US $12 for adults, US $6 for children 6-11. Children under 6 are free.

For details call (251) 433-2703 or email: [email protected] and visit www.ussalabama.com.

Peter Lynch is a UK-based travel writer regularly working for American and Australian newspapers as well as UK travel magazines. He is currently working on a guidebook to conservation volunteering, which is due out with Bradt Guides in late 2008.

- Life of a Champion: Exploring the Muhammad Ali Center in Louisville - April 19, 2024

- What It’s Like to Live as an Expat: Lake Chapala, Mexico - April 18, 2024

- Top 5 Spots for Stargazing in North Carolina - April 17, 2024