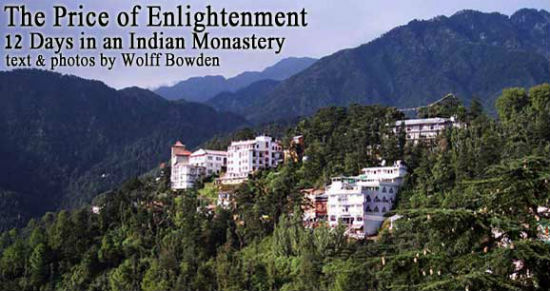

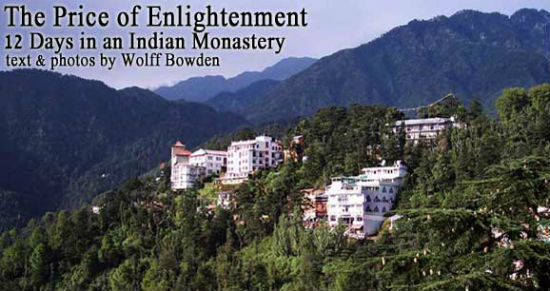

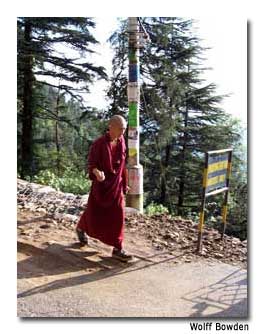

Day Zero: It takes all afternoon to let the rainy Himalayan nightmare sink in: I’ve hiked out of the charming, Tibetan hamlet of Dharamkot and all the way up a nameless mountain just to sign myself into a concentration camp. Actually, I signed up months ago, from Florida, via the Internet. Vipassana Meditation Courses fill up fast. They’re a surefire ticket to enlightenment for an unbelievable price: free.

All lodging, meals, instruction, chai and facilities are paid for by previous participants. But free comes with rules. Ten days of staggering silence. Men and women segregated. Cold plywood plank bunk beds. Four a.m. gongs. A miniature banana for dinner. No books. No journals. No iPod. No killing. No lying. No stealing. No sexual misconduct. Bucket showers. Hole-in-the-floor toilets. Oh, and meditation. Ten hours a day of sitting meditation, our backs burning like torches, our legs numb as pretzels carved in ice.

Day 1: At four, as promised, the gong goes off. I shake myself awake in my concrete block shoebox of a room and stumble up to the Dhamma Hall, or meditation room. Each meditator gets a firm, square cushion and we all sit facing the “teacher,” a small Indian man dressed in white. I close my eyes, and I’m in a dog kennel.

The 40 men around me are sniffling and snorting, belching and coughing. This disconcerting symphony dwindles as a stereo system booms a voice chanting Sanskrit.

This is the voice of S.N. Goenka, a Burmese leader of the rebirth of Buddha’s original path to enlightenment: Vipassana Meditation. For the rest of the day, we practice focusing all our attention on the sensation of our breath moving in and out of our nostrils.

Day 2: I wake before the gong with hunger’s claws in my guts. I meditate in my cell until 5 a.m., practicing the teaching of “anicha” or impermanence, realizing that the sensation of starvation will pass away as naturally as it arises. My body is a bundle of aches as I meditate through the day, envious of the gangs of mischievous monkeys splashing in the muddy, red courtyard.

Day 3: By two in the morning I’m thrashing around in my bed like a shark in a sea of fire. I’ve got the worst fever of my life, and I don’t want to die. To distract my mind from the pain, I focus on the face of a beautiful girl I left behind in America. At four I break the silence and whisper to a facilitator that I need help. He tells me to practice “Hana Pana” or breathing with a focus on the sensations inside the nose.

I’ll be back,” he says.

A few sweat-soaked hours later, he beckons me to the teacher’s quarters, but I’m so weak that I hobble along like Pinocchio.

“I need help,” I say to the teacher. “It might be malaria.”

Oh, this fever is very good, dear boy,” he says. “You are making great progress. Fever is only your negative karma rising to the surface. Be strong. Keep meditating.”

“I think I should take some medicine, too.”

“Yes, yes, yes! Medicine and meditation!”

The facilitator walks me to the check-in room, pries open a steel chest, hands me some Combiflam, and I’m knocked out in my cell for the rest of the day. When I wake, I meditate.

Day 4: After lunch, during a time for meditation in our cells, I hear a chainsaw in the room across my hall. It’s a big Indian guy. His snoring draws the facilitators to his door instantly.

“Let me sleep!” He shouts.

“You must meditate,” they whisper.

He slams his door in their faces. An hour later, he’s storming across the courtyard, a blue suitcase in each hand.

They’re leaving in droves now. First, one of the red-headed brothers from New Zealand. Then one of the Israelis. They’re gone before receiving the real Vipassana teaching. Tonight, we get it, at our video Dhamma Talk, a recording of Goenka on a television: Vipassana technique is a body scan of sensations from the top of the head to the toes and back.

Day 5: It feels like I’ve been here 50 years. I meditate “diligently and persistently,” as Goenka advises. For the first time, the restless, run-for-your-life feeling subsides and I think I might make it. The meditators around me look stricken, sick, depressed beyond belief. No one is smiling, so I do. I smile at the trees. At the pack of wild dogs that shows up in camp and wages war with the troops of monkeys. And I discover something: when you smile, your nostrils open wide and it’s easier to breathe.

Day 6: Everyone is sick. We’ve pushed our bodies too far. The Dhamma hall is a festival of hacking. It has rained every day and the nights have grown steadily more Himalayan. Half of the men walk around wrapped in colorful, Tibetan wool shawls. Mine is red.

Day 7: My meditations have begun to burn with an electric calm. I can now descend for an hour, barely noticing the flight of time. A new feeling of bliss descends, in spite of the ragged cough in my lungs, my yearning for a hot shower in a warm room down the mountain. I begin to fall in love with the nothing, the emptiness at the center of myself, at the center of the universe, at the center of every bit of matter in existence.

Day 8: So much meditation!

Day 9: Freedom is so close I can smell it. The meditation has deepened my peace; I find it hard to be upset about anything. A mosquito lands on my foot and I kill it, breaking one of the commandments of the camp: do not kill. Then I realize that all of us are killing plaque each time we brush our teeth.

Day 10: Our vow of silence is lifted after lunch, because we’re leaving for the world tomorrow. I meet the other men for the first time. We laugh about the madness of the camp, cursing and loving it. There’s one other American, from New Jersey. I think, of all the men, we Americans have come the greatest distance. From a society that revolves around the possession of things, we’ve wandered up the mountains to shed everything.

Day 11: Once we find the light within, we spread it. We drop rupees in the donation box so others can meditate as we have. We fire up our iPods and dance down the mountain, spreading out into hotels with steaming showers, sleeping for 12 hours, waking up in the world again, ready to spread our calm through the churning Indian streets. Even tomorrow, when a motorcycle crashes into me, ripping skin from my calf, I will not lash out at the driver. I will ask him, face to face, calmly, to drive more carefully. And I’d bet you a month on the mountain that he will.

If You Go

Vipassana Meditation Courses

www.Dhamma.org

- The Low-Key Magic of Ghent, Belgium - April 22, 2024

- Discover the Hidden Charm of Extremadura in Spain - April 20, 2024

- Life of a Champion: Exploring the Muhammad Ali Center in Louisville - April 19, 2024