The Great Lakes – Superior, Erie, Ontario, Huron and Michigan – are better described as “inland seas,” especially when compared to the likes of Lake Como, Lake Tahoe, Lake Mead, Lake Geneva and England’s Lake District.

The Great Lakes

Some 21 percent of the world’s surface fresh water is contained within the 94,250 square miles they occupy in America’s upper Midwest region bordering Canada and leading to the Atlantic Ocean. Lake Superior, alone, is the world’s largest lake, and Lake Michigan is the largest lake entirely within one country.

There is a reason it was a lake in New York named “Placid” instead of one of these deep giants, for they feature rolling waves, mighty winds, and brawny currents which have swallowed countless ships and claimed many lives.

In addition to the shipping and fishing industries, and the lakefront commercial centers such as Cleveland, Chicago, Milwaukee, Erie, Green Bay, Duluth, Toronto, Rochester and Detroit, the Great Lakes are a haven for tourists who spend summers on boats and beaches in places like Michigan’s Traverse City; Wisconsin’s Door County Peninsula; and Put-in-Bay on South Bass Island in Lake Erie. And while the fishing and frolicking and canoeing and kayaking are all part of the fun, caution must be taken.

Great Lakes Adventure Can Be Lethal

Vic Jackson’s new book “Crossing Lake Michigan in a Bathtub” is an anomaly. In 1969 the Lansing, Michigan man, on a dare, navigated 60 miles from Ludington to Manitowoc, Wisconsin in a 250-pound, cast iron tub buoyed by empty oil drums and powered by a 20-horsepower motor.

Jackson’s voyage, without lights or navigational equipment, was remedial and though successful, stands in stark contrast with the annual Chicago to Mackinac sailboat race which resulted in tragedy in 2018.

Crossing Lake Michigan with a crew aboard a high-tech racing sailboat, Jon Santarelli, a 53-year old experienced sailor, fell overboard as 20-knot winds and eight-foot waves battered the boat. Crew members reported he looked comfortable in the water but then noticed his automatic life jacket did not inflate. Six minutes later he went under the boat for the second time and then slipped below the surface never to be seen again.

The Great Lakes Water Safety Consortium reported more than 50 people drowned in the lakes in 2018; a grim fatality number on pace to be surpassed in 2019. There were people swept away at river mouths and boaters who fell into the lake or had their vessel overturned while some were simply beachgoers who were overcome by riptides.

Great Lakes Drownings

A majority of the Great Lakes drownings have occurred in Lake Michigan, likely due to the concentration of population near urban centers. In contrast with the ocean, Lake Michigan’s waves come in quick succession making it more difficult to stay above the freshwater – which offers no salt buoyancy.

A teenage girl in Grand Haven, Michigan, was lucky to be saved when she was swept off the pier and into turbulent Lake Michigan in July, 2019. A couple in a nearby boat happened to see her fall and managed, with great courage, to get close enough to pull her aboard without foundering the boat against the pier. The conditions were so bad that week even the annual Coast Guard Festival “Parade of Boats” had to be cancelled.

The maritime history of the Great Lakes is rich with wrecks of boats whose captain’s and crew didn’t have the luxury of canceling their voyages, and although somewhat grim, shipwreck diving and glass bottom boat tours are popular vacation experiences.

The maritime history of the Great Lakes is rich with wrecks of boats whose captain’s and crew didn’t have the luxury of canceling their voyages, and although somewhat grim, shipwreck diving and glass bottom boat tours are popular vacation experiences.

And most people know Canadian pop music star Gordon Lightfoot by his six-minute ballad: The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald.” His song was about a massive iron ore freighter which, in the mid 1970s, mysteriously and suddenly sank in Lake Superior during the “gales of November” and took 29 men with her only 15 miles from the relative safety of Whitefish Bay.

Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum is Both Fascinating and Somber

Bruce Lynn is the Executive Director of the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum located near the sinking on Whitefish Point which, had the weather not been so grim and dark that November evening, would have been within in sight of the Fitzgerald’s crew. Hauntingly, the museum is in a town called “Paradise.” Each November 10, on the anniversary of the Fitz’s sinking, the museum holds a ceremony during which the ship’s bell, which was recovered, is sounded 29 times in honor of the doomed crew.

Bruce Lynn is the Executive Director of the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum located near the sinking on Whitefish Point which, had the weather not been so grim and dark that November evening, would have been within in sight of the Fitzgerald’s crew. Hauntingly, the museum is in a town called “Paradise.” Each November 10, on the anniversary of the Fitz’s sinking, the museum holds a ceremony during which the ship’s bell, which was recovered, is sounded 29 times in honor of the doomed crew.

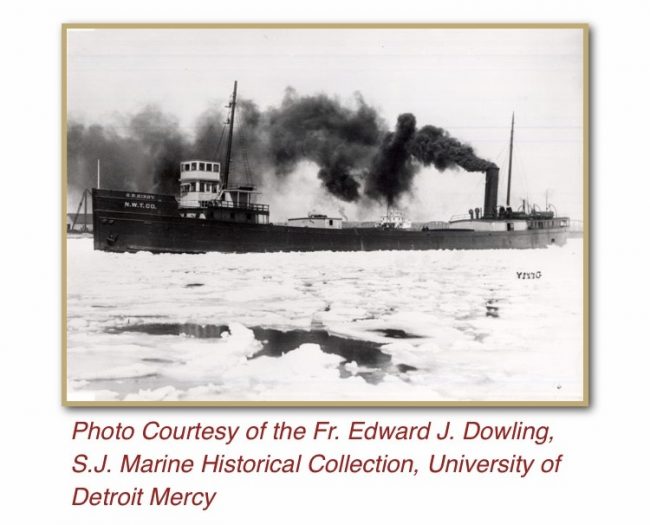

“The wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald freighter gets a lot of attention in the Great Lakes area but the tale of the S.R. Kirby is an important story, too, he said.

The Latest Shipwreck Find is Unique

The Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society recently discovered the wreckage of a steamship named the S.R. Kirby at the bottom of Lake Superior resting in over 800 feet of water near Eagle Harbor on the Keweenaw Peninsula.

“She sank on May 8, 1916 and was kind of an unusual little ship in that she was about 294 feet long, roughly, and was a composite steamship – meaning it had an iron frame and a wooden hull,” said Lynn of S.R. Kirby, which was built in Wyandotte, Michigan in 1890. The ship, with 22 men on board, left Ashland, Wisconsin bound for Cleveland towing a 352-foot steel barge loaded with iron ore.

Fierce Weather Moved in on the Ship

A weather station in Duluth, Minnesota clocked the winds of a storm that followed the S.R. Kirby into the lake at 72 miles-per-hour that day.

“It was a pretty rough storm but nothing she shouldn’t have been able to handle,” said Lynn. “But if you read the newspaper articles of the day they indicate the Kirby was overloaded. They only had about two feet of freeboard and that’s not a lot. If you start getting waves that are 10 or 20 feet high and winds of 50 to 70 miles-per-hour that’s pretty tough going. That’s ultimately what caused her to break up.”

Eyewitness and survivor accounts describe a quick end to the S.R. Kirby.

“There were several other ships in the area but one ship that was nearby that morning saw a wave hit the Kirby and they watched the ship break up and sink. They were able to rescue two crew members and the captain’s dog Tige,” he explained. “Lake Superior at any time is pretty cold and in May it is very, very cold water. The waves and the wind made it very tough to survive.”

One of two survivors, Second Mate Joseph Mudra, later reflected, “The steamer broke in two without a moments warning. As the ship went down, which took up so little time that I could scarcely believe my eyes, cabins broke loose and rafts floated. I did not see any of the men come up out of the forecastle, and while I saw some of them afterwards clinging to bits of wreckage, I believe most of them were caught in the forecastle and were unable to get out.”

Finding the S.R. Kirby Over 100 Years After Its Sinking

“We knew the general vicinity of the reports of where she had gone down so we searched the area with a sonar device made by a company called Marine Sonic which we tow behind a 50-foot research vessel called the David Boyd,” Lynn explained. “On our second attempt we were out there about five weeks and then were able to positively identify the sunken S.R. Kirby.”

What condition is the shipwreck in?

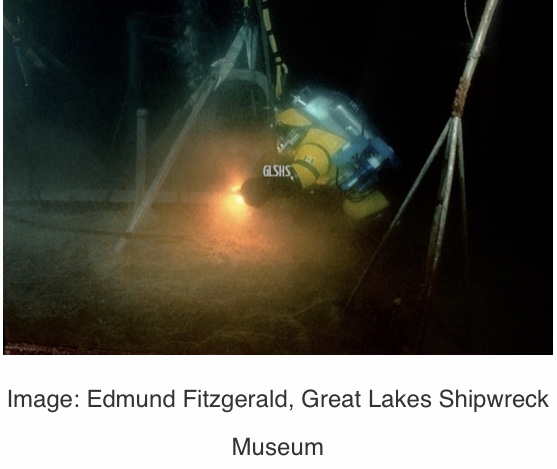

“It lies 830-feet down so no diver is going to go to that depth but we have an R.O.V. – a little remotely operated vehicle – that’s like a robot with cameras and high-intensity lighting. We were able to get it down there and get a really close look at all this wreckage.

The Kirby is in rough shape. It’s almost as if a small explosion had taken place on the bottom of the lake. It’s unlike any that I have ever seen in the way it is strewn across the bottom of the lake. But there are sections of the hull that show the iron framework with the wooden hull itself.”

The Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum

The S.R. Kirby will story will be told at the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum, which welcomes more than 75,000 visitors each season along “Lake Superior’s Shipwreck Coast.” The displays, a video theater, and the authentic lighthouse buildings bring dramatic shipwreck legends to life and tell the stories of the sailors and ships who braved the lakes. The Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum is open to the public seasonally from May 1 to October 31.

Michael Patrick Shiels is a radio host and travel blogger. Follow his adventures at GoWorldTravel.com/TravelTattler. Contact Travel Writer Michael Patrick Shiels at [email protected]

- Ashford Castle Hotel, U2’s Bono and Why Visting Ireland is So Entertaining - March 28, 2024

- Solo Travel to Oceania Cruise Ports St. Barth’s and Barbados Became Authentic Cultural Encounters - February 27, 2024

- Event Planning Star Tiffany Davis Visits 20 Beverly Hills Special Spots in 20 Days - February 18, 2024