Mount St. Helens, a volcanic peak in the Cascade Range of southwestern Washington State, has fascinated me since I was working for the Forest Service in the 1980’s.

The Cascade Range is a mountain region renowned for its chain of tall volcanos. They run north-south along the west coast of North America from British Columbia to the Shasta Cascade area of northern California. Mount St. Helens (8,364 feet; 2,550 m) is located 96 miles (154 km) south of Seattle, and 53 miles (85 km) northeast of Portland, Oregon in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest (named for the founder of the U.S. Forest Service).

Dormant since 1857, Mount St. Helens erupted on May 18, 1980 in one of the greatest volcanic explosions ever recorded in North America, measuring 5.1 on the Richter scale. The north face of the mountain collapsed in a massive rock debris avalanche. Almost 230 square miles (600 km²) of forest was blown over or left dead and standing. My co-workers joked that the explosion was merely Gifford Pinchot (1865-1946) lighting his 115th birthday candle.

On a bright September morning, more than two decades later, my first stop on a Pacific Northwest trip had to be to Gifford’s birthday candle. The Mount St. Helens’ Visitor Center at Silver Lake, located only a short distance from Interstate 5, was full of interactive exhibits that not just the visiting school children found exciting. One could move the earth’s plates to see how plate tectonics work ― the geological theory to explain the phenomenon of continental drift ― and go inside a model volcano.

The instructions of a working seismograph explained how eruptions were always preceded by an increase in seismic activity. I looked at the paper graph generated by the machine and saw hardly any ink. So I jumped up and down. The needle did the same and one-inch (2.5 cm) lines appeared on the paper. It did work after all. But there certainly had been no other seismic activity that day.

I went outside and marveled at the volcano from the overlook. There she stood in the distance with a white dome-shaped cloud camouflaging her high summit.

As I continued to drive about 40 miles (64 km) to Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument, the mountain played peek-a-boo with me. I crossed the Toutle River, which had been a raging river flooding the valley with rocks, ash and debris on that fateful morning of May 18, 1980.

Now, the river was merely a trickling stream in a gouged out canyon surrounded by massive white and gray boulders. Stands of evergreen trees proudly bordered the road. They boasted signs, attached by the timber industry, announcing the dates they were planted, thinned and projected for harvest. Separating the trees were white stumps of trees that had been decapitated in the 1980 blast.

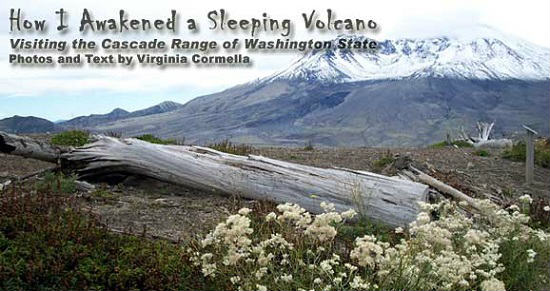

Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument was established in 1982 to protect 10,000 acres (40.5 km²) dedicated for research, recreation, and education. Everywhere I looked, I could see flowers, low bushes and small alder trees surrounding bleached decapitated stumps and downed logs. The monument is used as a living laboratory to determine the scope of Mother Nature’s recovery program from a volcanic explosion.

At the Coldwater Ridge Observatory, my first stop, nature’s rejuvenation program was dramatic. Below was the beautiful Coldwater Creek Lake formed when the volcanic debris of the eruption formed a natural dam to this previously free-flowing stream, Coldwater Creek. Jagged stone islands called hummocks were created when boulders hurled into the newly formed lake. Across the lake, Mount St. Helens stood majestically with the cloud still hiding the summit.

The Park Ranger explained that all the vegetation around us had grown since the 1980 explosion through natural processes. Long dormant seeds germinated when the competition for light was eliminated because older trees were burnt. Birds and wandering elk spread seeds through their scat. Wildflowers, bushes and alder trees reappeared. Western toads ― funny looking nocturnal amphibians with stocky bodies and short legs, who tend to walk rather than hop ― thrived because a layer of ice protected the tadpoles from the volcano’s fury. Once the toads emerged, they could multiply in peace. Their predators had fled or died in the blaze.

A boy asked the ranger: “Are we safe standing here? What’s to keep this volcano from erupting right now?” The ranger explained that the volcano is constantly monitored by seismograph. An eruption provides early warning when many minor earthquakes are noticed. He assured the little guy that there had been no tremors in a long time and that he was perfectly safe.

The Johnston Ridge Observatory, another 15-minute drive down the road, was named for a Geological Survey employee killed during the 1980 eruption. Across the ridge from the observatory was a view of the grey mountain with snowfields at the top. Below the snow to the left was a gaping hole, the caldera, a volcanic crater formed by the thrown ash, steam and magma of the 1980 blast. No vegetation covered the menacing mountain. A long pathway led to the caldera. Hikers trekked the path. Children ran and shouted. A herd of elk grazed undeterred by the boisterous children or the sleeping volcano.

Impressed, I left Mount St. Helens and headed further north towards Mount Rainier, another peak of the Cascades, all the while blissfully unaware of the growing seismic activity of Mount St. Helens. As I passed her again while driving down I-5, I turned on the radio. An increase of seismic activity with a swarm of minor earthquakes had been detected at Mount St. Helens. Had my jumping set off a potentially cataclysmic event?

For the next five days, I was oblivious to the increasing activity at Mount St. Helen’s as I toured the Oregon Cascades. Sometimes I heard snippets of radio coverage about increased seismic activity.

Arriving in Portland, the largest metropolis in neighboring Oregon, right at the southern border to Washington State, the city was abuzz about an imminent eruption. Seismic activity had elevated to a rate of three to four events per minute, with some events at a magnitude of 3.3. A volcano advisory was issued while I visited Portland’s botanical gardens. The docent pointed to the view. Behind the tall city buildings you could see Mounts Hood and Adams. Mount St. Helens was to the left. If we looked carefully, maybe we could see it erupt. And, at that very moment, the mountain actually did erupt.

The next morning, I headed north again past Mount St. Helen’s. Intermittently, I saw the majestic mountain against the blue sky. Nothing happened. As I turned west, I heard that the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) — a government agency studying earth sciences — had augmented the advisory to a volcano alert. It said that explosions from the vent, including “ballistic projections,” could occur without warning.

While I toured the majestic temperate rain forest of the Olympic Peninsula — the large arm of land in western Washington State that lies across Puget Sound from Seattle — Mount St. Helens erupted again with a steam and ash event. When I strolled through the nearby streets of Seattle, she erupted once more. But as soon as I flew out of the Washington State’s largest city, the USGS actually downgraded the status of Mount St. Helens to a volcano advisory again. Had my departure caused the reduction in seismic activity?

Mother Nature is beautiful, powerful and terrifying. Dangers lurk in the most majestic sights. Be careful where you jump. Who knows what forces you’ll unleash?

If You Go

After nearly 20 years of being dormant, Mount St. Helens woke up and began rumbling in September 2004. On October 1, 2004, the mountain expulsed an enormous amount of steam and ash into the air. Five days later, the U.S. Geological Service reduced the alert level, assuming that an eruption was not imminent in the next “minutes or hours.” While experts warn that an eruption similar to the one in 1980 is still possible, the chances are considered fairly low.

Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument

Washington State Tourism

www.experiencewashington.com

- Discover the Hidden Charm of Extremadura in Spain - April 20, 2024

- Life of a Champion: Exploring the Muhammad Ali Center in Louisville - April 19, 2024

- What It’s Like to Live as an Expat: Lake Chapala, Mexico - April 18, 2024