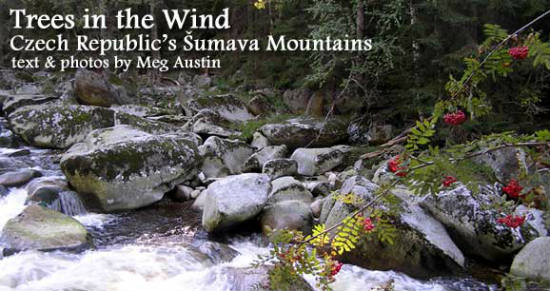

The approximately 120-mile long (200 km) mountain range that separates the Czech Republic from Germany and Austria is called Šumava, which in Czech means “a noise of trees in the wind,” “dense forest” or “murmuring,” according to folk etymology. But someone forgot to remind the river. The Vydra (“Otter”) pours down the mountains with the noise of an ocean, only unwaving — a constant reminder that sea once shaped this land.

Three million years have passed since Šumava and the neighboring Bohemian Forest belonged to the sea, making her, geologically, one of the oldest mountain ranges in Europe. She has grown egalitarian with age. With average heights of about 2,600 to 4,600 feet (800-1,400 m), the best views are not reserved for scramblers, but are accessible along gentle, well-marked paths.

Arriving in Šumava at all is perhaps the arduous leg of one’s journey. Though its trailhead towns are less than 90 miles (145 km) from the capital Prague, the trip can require up to five hours and multiple bus changes at stops that will be kindly remembered as remote.

I arrived at one such stop in the middle of nowhere 10 minutes too late for one bus and 16 hours and a cold night too early for the next. The last main town was about 12 miles (20 km) up the road, the next one an equal distance in the other direction.“Hospoda je tam,” the driver offered: “There’s the bar.”

The bar hosted only a mother and her small daughter. Within two minutes, the mother had wrested my 40-pound pack onto her own back, and 3-year-old Elishka was leading us across a bridge and into a garage that was really the local hydroelectric power plant. We balanced over planks and pipes and into an apartment off the back. There, Elishka stared from underneath pale eyelashes as Olga, her mother, cozied me into their living room–dining room–office–kitchen with a plate of fruit and cakes, and a cup of tea.

Olga sat and we talked as Elishka hid her face in her mother’s lap. Olga patted her daughter with one hand and her belly with the other: “Cekám.” Elishka would have a new sibling come spring.

Half-an-hour later a man arrived, tall, like Šumava’s sky-scratching spruce. Olga introduced her husband, and we piled into his truck. Where the Vydra meets the Křemelná River cars may go no further, and it is necessary to continue on foot to an inn 2.5 miles (4 km) up. Here I would have bid Olga and her family adieu, were not the very skinny man (bearing my very heavy pack), the pregnant lady and Elishka already hiking.

By the time we arrived, the sun had ducked behind the heavily forested mountains, and we seated ourselves next to a fire to enjoy beer, soup and supper. I was halfway into a potato when Olga’s husband turned to ask when I was born. In March, I sputtered. He meant which year.

“Dvanact-set-osmdesát-čtyři (1284),” I spat, failing to realize I’d just declared myself 722 years old. Olga supplied the correct number — devatenáct (19), not dvanáct (12) — and her husband continued: “So you were five … ”

In 1989 I was five, and then-Czechoslovakia was fed up. In the 40 years leading to the Velvet Revolution — the Czechs’ and Slovaks’ peaceful overthrow of Soviet rule — many attempted escape through these mountains. Some were shot, some shipped to the work camps known as gulag. Few made it safely across Šumava’s barbed-wire collar and into nearby Germany and Austria. For 40 years, these mountains were the Iron Curtain.

Olga’s husband spoke lowly and quickly, and I would have understood even less had Olga not footnoted his talk with simpler terms. But a sleepy 3-year-old and a dark hike ahead hastened their departure. I cried when I hugged Olga goodbye. She stroked my cheek and told me that her baby would come in March.

And then I stood alone by the ocean-river.

The Czechs are a nation of sailors without a sea. Landlocked in the heart of Central Europe, they have weathered more than 1,100 years of recorded history; three globe-changing occupations (the Hapsburgs, the Nazis and the Soviets); and an equal number of social revolutions in the past century alone.

They have learned to float amid storms that might have drowned a people whose customary greeting is anything other than Ahoy. Thus, the Czechs have simply channeled their yen for sea into a love ofpriroda (nature), natural places that allow one to feel infinity and insignificance.

The 75-mile (120 km) swath of Šumava contains nearly 200,000 acres (809 km²) of forest free of any major roads. The most valuable parts are protected in the Šumava National Park and Protected Landscape and the UNESCO Biosphere Reserve — a protected landscape in Europe. And to explore it as the Czechs do, it is necessary to carry a basket for collecting mushrooms along the way.

Czechs are great mycologists, scouring the forests for houby (mushrooms). If one happens to spot mushrooms within plain sight after 9 a.m., one may safely assume the houba in question is poisonous, as anything edible is, by this time, already on its way to someone’s kitchen.

The Pramen Vltavy, literally the source of the Vltava, the river that gives purpose to the beloved Charles Bridge in Prague, springs from these mountains. The paved trail leading there is a veritable pilgrimage for Czechs old and young, who navigate it from the shoulders of a parent or in flocks of shuffling seniors. The incline is modest, and the view at the summit minimal. A plaque marks the spot beside a symbolic well, shallow enough that an arm in a T-shirt might trawl the bottom for enough coins to call home.

Descending from here, a round little man in a bus driver’s suit beckoned me off the trail. He nodded back toward two female companions, one well-kept with artificially black hair and careful makeup, the other with rice-paper skin and a bun white as the Vydra’s rapids. He identified the first lady as Babička, Grandmother, and the second he called Prababicka, Great-grandmother.

With my new friends, I boarded a bus toward Antýgl. The driver and the Grandmother attempted to speak to me in German when my Czech failed, but the prababicka asked, in English: “What it is you would have to know?” I asked her where I ought to visit next.

“I am able to tell you,” she answered, and then smiled mutely until we reached Antýgl. As the bus stopped, she patted my shoulder and said, “It is here.”

In Antýgl an old man sat at a picnic-table with two dogs, a pair of spectacles and a rock. He stared at the rock.

Nearly an hour later, the man, the dogs and the rock all remained as they were. Only, the spectacles had moved from the table to the man’s face. Passing by him to return home, I realized he was mumbling something. I tried listening, but to no avail. His words were not for me.

Kierkegaard reasoned that unless we are able to make ourselves understood, we do not speak; we can talk all day and all night, yet remain speechless if we do not express ourselves such that another understands. But Šumava’s speech is the promise that no one who seeks conversation here will do so in vain.

If You Go

Šumava National Park and Protected Landscape Area

Šumava Mountains

www.Sumava.com

Czech Tourism

www.visitczech.cz

- Life of a Champion: Exploring the Muhammad Ali Center in Louisville - April 19, 2024

- What It’s Like to Live as an Expat: Lake Chapala, Mexico - April 18, 2024

- Top 5 Spots for Stargazing in North Carolina - April 17, 2024