It’s the dead of winter and I’m wrapped in fur and peering into the dark waters of Moyka Canal looking for a ghost. Almost 100 years ago, the Siberian mystic Grigori Rasputin, mortally wounded and left for dead, supposedly clung to the support rungs of Petrovsky Bridge before succumbing to the cold and slipping into the icy waters below.

It’s the dead of winter and I’m wrapped in fur and peering into the dark waters of Moyka Canal looking for a ghost. Almost 100 years ago, the Siberian mystic Grigori Rasputin, mortally wounded and left for dead, supposedly clung to the support rungs of Petrovsky Bridge before succumbing to the cold and slipping into the icy waters below.

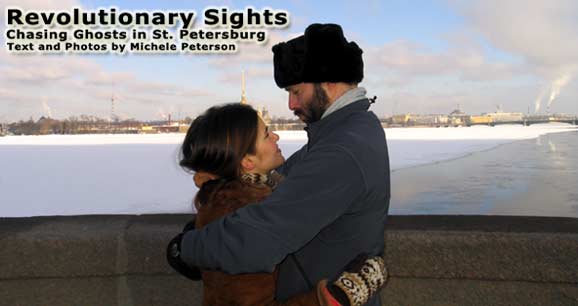

Although my muskrat fur coat is more woolly mammoth than chic, and I can’t really be certain where Rasputin dangled, when you’re on a do-it-yourself tour, you have to rely on your imagination to provide some of the details.

I’m at the midpoint of a self-designed haunted tour of St. Petersburg. Although most people visit the city during the white nights of summer when the streets throng with tourists, shoppers and musicians, when you need to travel for business you can’t always pick your travel dates. So I find myself in St. Petersburg in March.

What else to do besides read epics of passion and tragedy from the Russian revolution? After several long evenings indoors, I decide to investigate the city’s dramatic past and map out a walking tour, complete with warm-up stops.

All are within easy walking distance of St. Petersburg’s historic city center; no matter how fascinating the sights, when the average nighttime temperature is 17 °F (–8 °C), you don’t want to linger outdoors too long.

At sunset, I begin my journey into the gruesome past at Kazansky Bridge on Nevsky Prospekt, the city’s most glamorous street and main thoroughfare. Elegant women hurry past designer shops such as Versace and Hugo Boss, their long fur coats sweeping up clouds of sparkling snow in their wake. Babushkas huddle at the street corner offering scarves and mittens for sale.

Yet, just a few steps away from the bustle, eerie mists swirl over the frozen Griboyedova Canal where, rising like a ghostly blue specter, is my first stop — The Church of Our Savior on Spilled Blood, officially named the Resurrection of Christ Church.

Cheerful turquoise and lime-green domes mask its morbid history. It was built on the spot where Tsar Alexander II was assassinated on March 13, 1881. The church, with its 16th and 17th century Russian-style architecture and detailed mosaics, was built between 1883 and 1907 in the tsar’s memory.

Next stop on my itinerary of murder and mayhem is Mikhailovsky Castle, where one of Tsar Alexander’s ancestors met an equally violent death. Fearful of disloyal subjects, Tsar Paul I, successor to Catherine the Great, fortified his castle with moats and underground passages

But on March 23, 1801, a group conspiring to depose him from the throne entered the castle, found the tsar hiding behind a screen in his chamber, and assassinated him in his own bed. He didn’t even have an opportunity to use one of his secret underground passageways.

I trace his intended escape route across Nizhne Lebyazhiy Bridge to the Field of Mars. Commemorating the Roman god of war, the park is hidden behind greenery in summer. In winter, the St. Petersburg Eternal Flame is a focal point for pedestrians who huddle around it for warmth.

Erected in 1957, the fire burns in remembrance of St. Petersburg victims of wars and revolutions. It is believed that more than 40,000 Swedish prisoners of war, serfs and slaves died just constructing this city.

Earlier in the day I had toured the State Hermitage Museum’s vast collection of masterpieces — with Italian paintings by Leonardo, Michelangelo, Raphael and Titian, and French works by Degas, Gauguin, Matisse, Monet, Renoir and van Gogh — and strolled past opulent residences that line streets carved out of the bogs and swampland.

Now by night, those facades of lithe nymphs and muscular atlases seem to wrap snowy arms around the neoclassical columns as though seeking warmth offered by their rosy tones.

Back on Nevsky Prospekt, it’s time for a warm-up stop at the Literary Café. Even it has a tragic past. Now known for its fine dining and classical music, it was once the center of the city’s literary society, a gathering spot for writers and poets such as Fyodor Dostoevsky and Alexander Pushkin.

On a winter evening in 1837, the 37-year-old poet Pushkin, at the height of his literary career, set out from the Literary Café for a duel in the snowbound countryside with Baron d’Anthes, an admirer of his wife. Pushkin was mortally wounded defending her honor, and died on Feb. 10.

After a shot of vodka, I head to the blood-stained grounds of Decembrists Square, the site of Russia’s first revolution. Here, on Dec. 14, 1825, a small group of rebel officers staged a coup d’état protesting the accession of Nicholas I to the throne.

Several thousand troops attacked and executed many where they stood. Today, a statue of the Bronze Horseman, a ghostly specter that inspired Alexander Pushkin’s epic poem, dominates the area.

Across the square is Hotel Astoria (39, Bolshaya Morskaya). Despite its elegant interior and impressive view of St. Isaac’s Cathedral, it also holds a bloody secret from the past. On Dec. 28, 1925, Sergey Yesenin, a 30-year-old Bohemian Russian poet, hanged himself in the D’Angleterre Hotel, which was annexed to the Astoria during renovations in 1991.

In a particularly gruesome farewell, he painted a goodbye verse on the walls in his own blood. His avant-garde lifestyle reached mythic proportions after his death and even today continues to inspire imitative suicides.

I continue south to Moyka Canal, the site of Rasputin’s demise. Legends say that on Dec. 29, 1916, the long-haired guru to Russian aristocracy and confidant of Tsarina Alexandra Romanov, was lured to nearby Yusupov Palace, fed poisoned cake, shot and then tossed into these waters. Today, listening to the ice floes crack, while wrapped in fur like a heroine from Doctor Zhivago, it’s easy to imagine his ghost is nearby.

Still, I can’t help but be disappointed. I had somehow expected more of a legacy from the so-called “mad monk” whose sexual and spiritual powers had threatened the stability of the Russian Empire.

I step inside the Idiot Café — named after Dostoyevsky’s novel — next to St. Isaac’s Cathedral, and order a bowl of borscht, a traditional beet soup, to warm up before investigating further. In the flickering candlelight, I read in the local newspaper about Russia’s first sex museum. The new museum of erotica opened in May 2004 in St. Petersburg.

“There is one exhibit we are especially proud of,” reports Igor Knyazkin, the museum’s founder. It is the perfectly preserved, 11-inch (28 cm) sex organ of Grigori Rasputin. I realize that my quest for more evidence of Rasputin need go no further. The exhibit had already captured a remnant of St. Petersburg’s mysterious past. I decide to settle for a glimpse of his ghost.

If You Go

St. Petersburg Tourist Guide

www.saint-petersburg.com

State Hermitage Museum

www.hermitagemuseum.org

Russian National Tourist Office

www.russia-travel.com

- How to Get Around in Sydney: A Local’s Guide to Traveling Around Sydney - April 24, 2024

- The Low-Key Magic of Ghent, Belgium - April 22, 2024

- Discover the Hidden Charm of Extremadura in Spain - April 20, 2024