As the plane descended toward La Paz–El Alto International Airport, I knew what it was that Neil Armstrong felt as he lowered Apollo 11 onto the Moon. Hidden among the seemingly never-ending peaks and valleys of the South American Andean ridge, La Paz is among the most unlikely capital cities. It sits in a giant, bowl-like valley where sharp ridges and conical summits meet the altiplano — a vast expanse of mountain plateau desert.

As the plane descended toward La Paz–El Alto International Airport, I knew what it was that Neil Armstrong felt as he lowered Apollo 11 onto the Moon. Hidden among the seemingly never-ending peaks and valleys of the South American Andean ridge, La Paz is among the most unlikely capital cities. It sits in a giant, bowl-like valley where sharp ridges and conical summits meet the altiplano — a vast expanse of mountain plateau desert.

Landing an aircraft in El Alto, which spills dramatically from a shelf down into a valley where La Paz is situated, is no easy task. The city lies at an altitude of 13,615 feet (4,150 m). I had the fortune of sitting next to a Bolivian flight engineer named Jorge, who reassured me that it was perfectly normal for the wings of the plane to be vertical to the ground as it u-turned, circling slowly over the city, descending enough to be able to hit the runway head on (so to speak).

“Being the world’s second-highest international airport, and with such a complicated landing, pilots need special training to land in La Paz,” Jorge informed me moments before touch down. “NASA even does testing up here.”

Still feeling somewhat tense from my emergency landing on a different flight the day before, I wasn’t sure if this was a good or bad thing to know. As I dared myself to look out of the window, however, my fear took a backseat to complete wonderment.

To look down on this harsh, rugged beauty, so unfathomably vast and inhospitable, conjured images of far-away worlds. The view was simply breathtaking, a state I was to become accustomed to in Bolivia.

A favorite conversation topic among South American travelers is the degree to which altitude sickness renders them useless for their first few days in Bolivia. While I must admit I thought it all to be a bit of traveler’s hype, upon stepping off the plane I was instantly and disconcertingly proven wrong.

With the feeling of walking across the deck of a ship in a force 5 gale, my traveling companion and I managed to get our throbbing heads and nauseated stomachs into a hostel in the center of La Paz. Twenty-four hours later, breathless and weak, we emerged to discover that we had in fact not landed on the Moon, but had instead found ourselves deposited in a bygone age.

There seems to be almost too much going on all at the same moment in La Paz to be able to take any of it in. The deafening noise of the smoldering traffic and seemingly aimless shouting coming from every possible angle seem to echo off the walls of the bowl in which La Paz is shoe-horned.

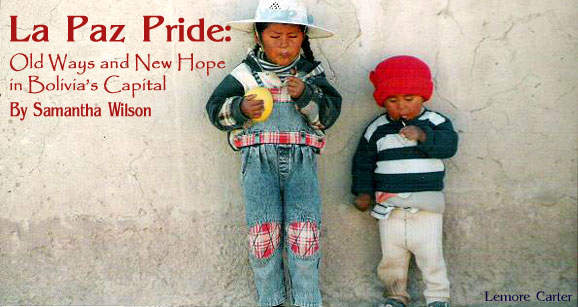

Women waddle down the street staggering under the weight of their multilayered traditional dress, bowler hats balanced precariously atop their heads, baskets containing their livelihood in each hand and a small child slung over their backs.

The lights of El Alto, the cities’ poorest favela-style (shantytown) district, twinkle as the buildings defy gravity, clinging to the sides of a vertical cliff, their smog-blackened facades closing in on the narrow, vertical lanes that radiate outward and upward from the central main street. Makeshift markets, stalls selling everything and nothing, litter the streets. Balaclava-masked shoe shiners, implying a more sinister profession, grossly outnumbered shineable shoes.

After acclimatizing not only to the thin air, but to the energetic bustle of the city center, it was time to find out what hidden secrets this hectic, desperately developing city had to offer.

Just out of sight of the main street, so alive with everyday activity, throngs of people and chaotic traffic, the Witches’ Market is as unusual a sight as they come. True to its name, the Witches’ Market is a collection of stalls squeezed into tiny, cobbled, colonial-style lanes laden with treasures to fill any cauldron.

Coming across my first dried llama fetus for sale, I must admit I was slightly taken aback. Seeing my look of confusion and morbid fascination, a small, elderly face wrapped in layers of colorful material smiled understandingly.

“It is for luck,” the lady told me from her seat on the pavement behind her stall, “to be buried under the doorstep of a new house.” Dried frogs, Bolivian armadillos and naked coupling figurines, each with its own powers, hang from shop doorways and stalls, creating an eerily mystical ambiance, like something from a Harry Potter novel.

Like following a clueless treasure hunt, weaving in and out of the labyrinthine lanes and courtyards, I stumbled across innumerable craft shops selling alpaca fleece garments, needed (and recommended) for an Andean winter. Tiny restaurants nestled into corners of once–colonial mansions served warm soups or llama steaks, a shop drowned under the volume of its handmade musical instruments, most destined never to be sold.

While Sucre, farther south, is Bolivia’s official capital city, La Paz has been the actual center of government since 1898. In La Paz’s Plaza Murillo, in the heart of the city center, the Government Palace and a vast cathedral tower over the bustling, poverty-stricken, colorful crowds below, acting as a constant antagonist in Bolivian life.

La Paz translates as “The Peace,” a bitter irony in a country plagued throughout history by conquest, liberation, poverty and government disputes. Any local, given half the chance, will enthusiastically regale visitors with stories of corrupt governments, poverty, scandal and hardship.

“Bolivia is, minerally, one of the richest countries in the world,” I was told by a group of elderly Bolivian men in a local café, “but where is this money? The government has it, that’s where,” their attention only distracted from their foreign audience by the television set behind them showing a live Bolivia-Peru football game.

But this country has refused to suffer in silence, protests and road blockades having become part of everyday life. Walking through the center, I looked on in fascination as thousands of demonstrators marched by in a Mardi Gras–style protest, drums banging and people chanting anti-government slogans.

While this, and many other, protests are a peaceful show of democracy and a vent for built-up anger and feelings of abandonment, many others are not so. Stories of buses being attacked, their windows smashed and occupants injured, trains screeching to a halt as crowds gathered on the line and the transportation network of entire cities ground to a halt, are daily news.

Piecing together the puzzle that is La Paz’s character produces a complex picture. In a country so stricken by poverty and hardship, it would be easy to think that people have lost hope, but this is not the case in La Paz. Smiles come from the most unlikely candidates: the old man who sits among the pigeons, begging; the woman sitting on the corner pavement selling finger puppets; or a young teen with nothing else to do. But despite La Paz’s obvious street poverty, it is a city fighting desperately to keep up with the rest of its continent.

Modern buildings rear their heads between the colonial architecture, a constant reminder of the city’s Spanish roots. Fledgling international businesses give hope of prosperity. Passionate and energetic, La Paz’s residents have a lot to say for themselves, and say it loudly. Whatever their future holds, it can be said for sure that the people who give La Paz its character will take it with pride and dignity, and certainly won’t go down without a fight.

If You Go

Bolivia Tourism

www.boliviaweb.com

- Life of a Champion: Exploring the Muhammad Ali Center in Louisville - April 19, 2024

- What It’s Like to Live as an Expat: Lake Chapala, Mexico - April 18, 2024

- Top 5 Spots for Stargazing in North Carolina - April 17, 2024

Great blog Samantha! Thank you for sharing it with me a little while back on twitter (@Proj_Abroad_UK). I love where you say “Passionate and energetic, La Paz’s residents have a lot to say for themselves, and say it loudly.” That certainly rings true. It’s a destination I would love to return to! 🙂