It’s hard to imagine a more idyllic, almost mystical setting. We are deep inside the Fijian hinterland of the main island, Viti Levu. It’s a good hour’s drive along a corrugated, dusty back road from the coastal town of Sigatoka.The village where we sit is named Dubalevu and it’s located centrally in an area referred to as Fiji’s salad bowl, so called because of the bountiful supply of fruit and vegetables that are farmed here, bound for the markets of Sigatoka and beyond.

For my wife and I this is familiar territory. She is a Fijian national who now calls Australia home. We have brought a group of 10 friends on a two-week vacation with the intention of introducing them to the real Fiji, primarily through a diverse range of cultural activities.

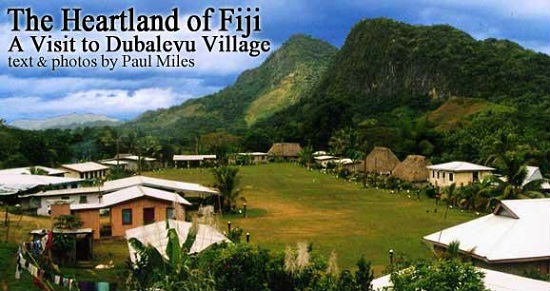

They seem to look down on Dubalevu with a sense of proprietorship. It is a common sight to see the village shrouded in mountain mist, clinging to the spires like curtains. Dubalevu Village sits alongside the Sigatoka River, a large meandering waterway that, even this far inland, is 100 yards (91 meters) wide. By the time it reaches the sea it will be five times broader. Looming large over the village are several ominous-looking granite outcrops.

Today is not one of those days. A strong, vibrant sun shines down on us from a cloudless sky.

We are midway through the welcome ceremony, ensconced in the bure of the village chief. The bure, a large thatched roof building, is a traditional Fijian home. Our group sits nervously on the floor atop woven mats, a common home accessory here. The locals try to put us at ease but little English is spoken throughout the traditional Yaqona Ceremony.

Yaqona, or kava as it is referred to in the Western world, is an unappetizing brew. It’s made by infusing cold water through a muslin cloth, filled with the powdered kava root. The resulting light brown mixture is collected into a tanoa, a large wooden bowl.

Everyone present is expected to partake. A bilo, a communal cup made from the casing of a coconut, is filled from the tanoa. One by one the guests and locals are asked to drain the bilo in one long swallow. A routine series of hand clapping accompanies all parts of the ceremony.

Outside, a series of metallic banging noises echoes around the village. Anxious looks furtively come my way from some of our group. It’s a sound that resonates around Fiji every day. It’s the sound of the dried kava root being pounded into powder form by using an implement resembling a crowbar. Fortunately for our group, one small drink from the bilo is all we’re obliged to take today.

Soon we are back outside in the bright sunshine and its intensity reminds us how naturally cool it was inside the chief’s bure. The village compound is about the size of a soccer pitch and a lush, verdant grassy area is surrounded by 20 or so homes arranged in roughly rectangular fashion.

Young children abound. They’re constantly at our feet, laughing and joking, no doubt hoping for a treat from their strange guests. Their hands are soon full of chocolates and other delights.

Everyone is captivated by the preparation of the lovo, the underground oven. Pork, chicken, a selection of local vegetables, such as cassava, taro, yams and breadfruit, are wrapped and placed on the hot coals before all is covered by large taro leaves.We are then shepherded across the village green to the community hall building. Later that afternoon we will be treated to an early dinner.

At a leisurely pace, we head for the river where the languid water flows serenely away from the village toward a distant bend. Thick undergrowth strangles the river banks on both sides. The granite hilltops now stand over us like sentinels. A bilibili, a large bamboo raft, awaits us as we are escorted by what seems like every child in the village.

Despite appearances, the river is not deep and in most parts, those swimming alongside can stand. The cool, enticing water proves too tempting for most as the afternoon humidity engulfs the river’s interlopers. By the time the bilibili reaches its destination, a few bends downstream, there are more people in the invigorating water than on board.

The trail back to Dubalevu Village winds through a maze of farm land. Tobacco crops are everywhere. As we near the village we are greeted by a copious amount of tropical fruit. Bananas, pineapples, mangos and pawpaw abound. The heat and the increasing hordes of mosquitoes are soon forgotten. The youth of the village toil under the hot afternoon sun, sweat glistening on their fit, muscular torsos.

Back on the village green, the population of children seems to have grown. The local schools are now out and news of our presence has quickly spread. Inside the hall, the food from the lovo has been neatly arranged on plates on the floor. They sit atop a beautiful tapa tablecloth that is decoratively adorned. Pitchers of fresh fruit juices are at hand for everyone.

The pork and chicken dishes are complimented by fresh fish in coconut milk and palusami, a corned beef and spinach offering. Tentative pickings by the guests rapidly give way to whole hearted feasting of the sumptuous foods, much to the delight of the villagers.

Barely has the last mouthful been gorged when the music starts. Laughter and enthusiastic dance moves by the women and children soon spread. It isn’t long before the guests are drawn into the dance activity. Excuses of bad backs fall on deaf ears. Soon everyone is on their feet doing a form of tribal line dancing.

Those who haven’t clutch embarrassingly at their fast disappearing sulus and modesty. The laughter permeates the entire village.Laughter fills the village as our sulus, a wrap around garment worn out of respect by the visitors, begin to slip forever downward. Those who have discreetly worn them over the top of their own clothing are now thankful.

Before long, under lengthening shadows, it is sadly time to leave. A cool breeze has sprung up as if on cue to cool the weary dancers.

Laughter is soon replaced by tears. New friendships are soon to be broken by the tyranny of distance. Our minibus edges out of Dubalevu at snail’s pace, due mostly to an infinite posse of waving, smiling children. Smiles and tears are in equal proportion both inside and outside the vehicle.

If You Go

Sigatoka, a service town, is an hour and 15 minutes drive from Nadi International airport. It is the gateway to the Coral Coast where most of Fiji’s main island resorts are located.

Hotels such as The Outrigger Resort, The Fijian Resort, The Hideaway Resort and the Bedarra Beach Inn can organize Village tours for visitors.

Fiji Visitor’s Bureau

www.bulafiji.com

Paul Miles resides in rural Victoria, Australia with his wife, Sereima and their two-year-old daughter, Kelera. An experienced world traveler throughout Europe, North America, Hong Kong and South Africa, he has concentrated on the South Pacific Islands for recent travels.

- The Low-Key Magic of Ghent, Belgium - April 22, 2024

- Discover the Hidden Charm of Extremadura in Spain - April 20, 2024

- Life of a Champion: Exploring the Muhammad Ali Center in Louisville - April 19, 2024