A Day At Mana Pools National Park

The sun had reached its zenith, and it was siesta time. My friend, Mia, and I saw elephants a little distance upriver.

Against the advice of our guide, Englibert, we walked toward them to get a closer look. At a spot with a good view, I climbed a small tree and stood in a fork five feet above the ground.

Farther off, a second group of elephants ambled near the river. Some 200 baboons napped, suckled infants, or wrestled, screaming, in the dust.

Several, like me, stood watch in trees. A large herd of gazelles and a half-dozen warthogs grazed placidly.

Then a bull elephant in the closest group of pachyderms moved toward us. Mia slipped back toward camp while I stayed and watched.

The bull ate shrubbery on a trail leading alongside my tree, then it was too late to move. As he passed downwind six feet (2 m) away, he stopped eating and sniffed.

I could smell him, too. He had an odor as big as his body; a spicy, rich scent like a teenage boy’s bedroom. He paused. I kept quiet (except for my heart) and he moved along.

The other elephants came down the same path and, like the bull, seemed anxious when they passed by me, but they didn’t do anything rash, and neither did I.

Then all the animals started to move off. Antelopes went all at once. Warthogs trotted, long, tasseled tails sticking straight up.

Baboons straggled out with the lookouts bringing up the rear. I heard Englibert yell, “You can come down now.”

He had been worried that I might panic and try to run, or that the elephant would attack. He had gotten out his gun just in case, and watched from a distance.

The Zambezi River

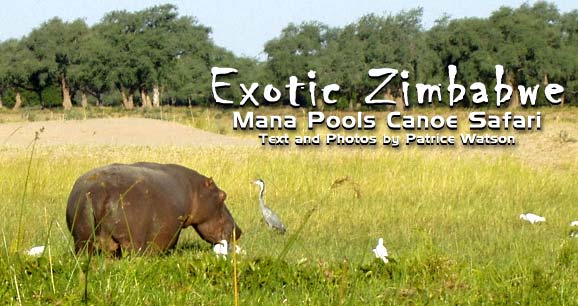

I was on a canoe safari in Mana Pools National Park, a spectacular World Heritage site in the north of Zimbabwe.

The Zambezi River, which divides Zimbabwe from its neighbor, Zambia, forms its northern boundary.

The river draws many wild animals, especially in September and October, the end of the dry season. One of the best ways to experience the river and its wildlife is in a canoe.

I’d met two women in Harare, Amy and Mia, and we had signed on with Kasambabezi Safaris, which provided transport, a guide and all our equipment and provisions for about US$ 100 per day.

Our guide, Englibert, and a driver met us in Makuti, three hours from Harare.

When we reached the river, we unloaded the truck and packed the canoes, then Englibert gave his safety and paddling spiel: hippos, those great vegetarians, pose the main danger to canoeists.

They submerge when threatened, then surface suddenly, potentially capsizing the canoe.

A panicked or angry hippo might attack a canoe. We must watch for them, give them time to move to the deep water, and pass them along the bank, in the shallows.

Crocodiles are only a problem to people in the water or on the banks. No swimming! Likewise, the shore animals are only dangerous when people are ashore.

Our Canoe Safari

We paddled off in two canoes. The river was broad, perhaps a half-mile (500 m) wide or wider, and as steady and smooth as a highway.

The banks and many islands were luxuriant with a thick carpet of grass studded with immense fig and wild mango trees.

As it runs through a desert-like environment, the river was warm. And it was clean. I would happily have swum in it, except for the crocodiles.

The sun was blazing, and we had three hours of hard paddling, then a fly-infested lunch stop, before we reached our camping spot, on a pleasingly breezy sandbar.

Englibert was a good cook. Dinner was a stir-fry of beef, onions, tomatoes and at least three different vegetables, with rice, accompanied by wine. After dinner, Englibert told stories of his life as a guide.

He told tales of hippo and crocodile attacks with great enthusiasm, but mostly he talked about everyday economics: living though a slow-motion economic collapse, working in an industry that has almost disappeared.

While we had tents with mosquito netting, I slept outside, where it was pleasantly cool. With no moon and no artificial light for miles, the stars were brilliant.

I heard only the murmur of the river, the calls of night birds and animals, and the occasional whoosh of air on wings.

Every day we started out at sunrise, after tea and cereal. After paddling for four hours, we stopped for brunch and rested for a few hours under some shady trees, high on a bank, with a good breeze to keep away bugs.

We had tea and a snack before setting off again, paddling until nearly sunset to camp on a bare sandbar.

Timing is critical: From sunrise to sunset, a sandbar is too hot. A bare sandbar lacks privacy, but there are no mosquitoes.

As we paddled, the Zambian escarpment — steep, rugged hills cloaked in dense, scrubby bush — rolled by on the north, and to the south, in Zimbabwe, a flat flood plain extended for miles. This stretch is national park land, with no human habitation.

On the Zambian side of the river bank, however, we saw occasional huts, some of brick, some of poles and clay.

The Surrounding Environment

Near these huts, people fished, bathed or washed clothes in the river. Zambian fishermen poled their way across the river, standing upright and solitary in their dugout canoes, which were nearly as invisible and quiet as crocodiles in the water.

Baboons and vervet monkeys scampered along riverbanks and island shorelines, and herds of elephants, African buffalos, zebras, gazelles, water bucks and impalas grazed.

The antelopes and zebras moved away at our approach, but the buffalos and elephants stood and watched us glide by. A buffalo has a very withering glare.

The park is a magnet for birds, with more than 380 species found here. We saw storks, egrets, ibises and cranes fishing in the shallows or perched quietly.

There were also numerous geese and ducks, and a great variety of shorebirds, as well as many different types of swallows and beecatchers; several types of kingfishers; and many eagles, including the Zimbabwean national bird, the fish eagle.

Crocodiles — solitary and motionless in the water or sunning on the bank — were a common sight as we paddled.

Sometimes when we were on the bank, one would station itself nearby in the river to watch us. Never once did we see throngs of them churning up bloodstained river water.

Hippos dotted every stretch of river. We wove our way through them. When we saw a group standing in the shallows, we would wait upstream.

They would study us for a while, in silence, their huge, comically deadpan faces turned toward us.

Then they would slowly move to deeper water, submerging when we started moving and resurfacing after we passed.

As we paddled away from them, we would hear them splashing and calling, tuba-like.

Once we spent half an hour entirely surrounded by 20 glumly indecisive, muttering hippos. Eventually they moved off and we were free to go.

Hippos stay cool in the water all day, then come ashore to graze after sunset. One blundered into our camp one night, adding to our adventures.

I heard him climb out of the water nearby. Ever-alert Englibert clapped his hands, and the creature froze, then returned to the river with a huge splash.

If You Go

Kasambabezi Safaris

P.O. Box 279, Kariba, Zimbabwe

Phone: 061-2573

Mana Pools National Park

www.off2africa.com

Travel Guide to Zimbabwe

www.places.co.za/zimbabwe

- What It’s Like to Live as an Expat: Lake Chapala, Mexico - April 16, 2024

- Travel Guide to Greece - April 16, 2024

- A Portugal Getaway: Four Days in Lisbon and Sintra - April 16, 2024