The airline officials check our baggage very carefully. They X-ray it twice, once before passport control and once after. They open our hand luggage, rifle through our toiletries and delight when they finally discover and confiscate the batteries in our camera. Later, on the plane, we can’t help feeling that not everyone was treated equally. Across the aisle, an old lady sits bundled up in shawls, her sculptured face peeking out from beneath a woolly pink hat, her hand grasping a silver prayer wheel. Engraved with Sanskrit, inlaid with coral and bearing a one-foot-long metal spike, it is a lethal weapon to be respected.

Thankfully, views of Everest soon distract us, and three hours later we arrive without incident. Now it’s the turn of youthful officials — dwarfed by their too-large uniforms and peaked caps — to study our documents.

“The Lhasa Airport of China,” muses my husband, reading the gold lettering on the terminal building, “no mistaking who’s in charge here.”

As we travel toward the city behind the tinted glass of a Toyota 4X4, documentary-style images rush past the window. Blizzards of dust race across a barren wasteland. Whitewashed houses stand like mini fortresses.

Prayer flags strain from rooftops like bunches of summer flowers. Pancake-like rounds of yak dung — a source of fuel — plastered to walls, dry in the sun. Beside the road, a 50-foot-high (15 m) rock carving of Buddha looks on serenely as prayer scarves decorating the rocks blow in the wind like crepe-paper streamers.

Children play in the dust; cyclists slouch low over ancient handlebars; and workers are piled high on rickety, lopsided carts. We gaze in astonishment as a pilgrim, on his way to Lhasa, places his hands together in prayer, touches his forehead, throat and heart, then lays full length on the ground. Rising, he steps forward and starts all over again. This is the Tibet we want to see — a country where ancient customs and practices still provide an awesome spectacle.

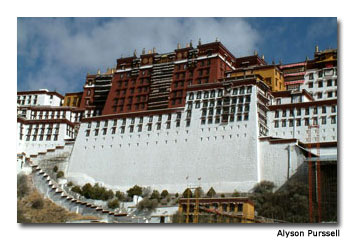

Lhasa is a modern Chinese city. We are greeted by the sight of wide roads, neon lights, shops, banks, offices and restaurants. Then we see the Potala. The huge, haunting fortress fills the sky, its ancient walls radiating brilliance. We strain our necks to absorb its enormity. It’s a fort, a palace, a monastery. It’s where Dalai Lamas ruled, and monks repelled the conquering armies of China, Mongolia and Nepal. If one image defines the nation, this is it.

Tashi, our guide, is our link with both past and present. His greeting, tashi deli — “hello,” “how are you,” “good fortune,” all rolled into one — is accompanied by an infectious smile. A 21st century Tibetan, he wears jeans, a smart jacket and polished black shoes. His mobile phone is never switched off. He speaks perfect English and German.

His knowledge of Tibetan history and culture is impressive. He would love to travel abroad, but knows he has as much chance of going to the moon. He wonders if we’ve ever seen the Dalai Lama, or the movie Seven Years in Tibet. He’s hungry for information.

Our hotel is in the Tibetan quarter, where rickshaws bump up and down the cobbled alleyways and yak butter is sold by the bucketful. The children here are wise to new arrivals. The local radar targets us, and small grubby hands are thrust in our direction.

We shake our heads, mouth the word “sorry,” and carry on walking. They point to their mouths, say lolly (British for lollipop), and start tugging at our sleeves. Tashi tells us not to give to beggars. Twenty-four hours later the same children have given up and moved onto the next pack of new faces.

For all its glorious symbolism, the Potala is not the beating heart of Tibet. That honor belongs to a temple situated two kilometers east. Here, surrounded by streets that are more Tyrol than Tianamen, shops more Kathmandu than Kensington, we find the Jokhang Temple.

Lit only by the flickering light of a thousand yak-butter lamps, the air within is oppressive and rancid. Rats scuttle between offering bowls of tsampa (roasted barley-flour porridge), and pilgrims chant mantras as they shuffle between jewel-encrusted shrines. Gazing, stroking, praying, they press bank notes into the Buddha’s golden hands. Monks in red and orange gowns sit cross-legged in recesses, on hand to receive prayers for loved ones and help them on their way with a cash payment.

Blinking, we emerge from the temple onto the roof overlooking the vast expanse of Barkhor Square, which has already had its cobbles replaced. A large, flat, gray expanse, it seems only to be waiting for basketball courts to be marked out. Around its perimeter, market stalls and street vendors provide a frieze of color, and pilgrims and tourists barter over prayer wheels and turquoise jewelry. In the square, beaming stall-holders ask us only to “looky, looky.”

A young girl approaches, walking across the square, and asks if she can practice her English. Soon we are surrounded. “What’s your name?” “Where you come from?” Young and old are eager to practice English lesson number one.

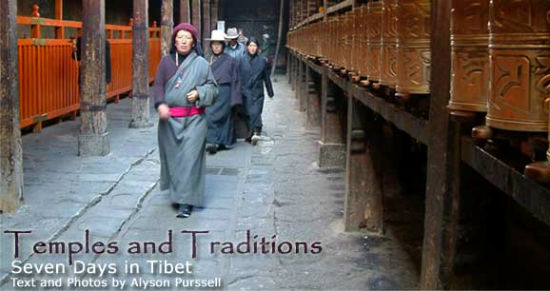

Later we join the throngs of people striding purposefully on their pilgrimage around the Jokhang Temple. Jeans, fleece, woolen gowns, cowboy hats, balaclavas, embroidered aprons and quilted waistcoats are all acceptable attire. Some wear sandals, but the footwear of choice is Nike. Halfway around, the cobbles start to disappear as men armed with pick-axes and shovels pry them from the ground. We ask a shopkeeper why the cobbles are being removed. “Flat surfaces — better for walking, better for cycling,” he replies. Ancient traditions are all very well, but practical living wins out.

At the Sera Monastery — which was established in 1419 — on the outskirts of town, we watch, enthralled, as dozens of young novices learn the art of debate. Senior monks debating with novices emphasize their points by raising their right hands high in the air and slapping them down onto their own outstretched palms. Above the din we ask Tashi what it’s all about.

“They debate the meaning of ‘big’,’” he replies, listening carefully, but it seems he’s as much in the dark as we are. Rounding the corner, we encounter a scene we can all understand: A young monk talking on a mobile phone. Later an elderly monk approaches and asks to look in our guidebook; he wants to see if his picture has made the latest edition.

We spend seven days in Lhasa before setting off on a journey that will take us overland to Kathmandu. We had arrived in Tibet expecting to find that Chinese influence had destroyed what was unique to this nation. Yet we leave believing that Tibetan fortitude has triumphed over adversity. Tibet has seen more changes in the past 50 years than in the previous 500. Yet her people seem to have accepted these new ways while holding fast to their ancient and wonderful heritage.

If You Go

www.tibettour.org/chinatibettoursite/moban/index.asp

- Top Things to Do with Kids in Kauai, Hawaii - January 13, 2024

- Cinnamon Bay Campgrounds, U.S. Virgin Islands - January 10, 2021

- Colorful Colonia del Sacramento, Uruguay - January 9, 2021