They say that you can’t go home again; that things always change, so it’s no use trying to recreate the past. I don’t want to revisit the past, really, but rather the city that helped to form me.

That is why I’m stretched out on a narrow bunk bed on the night train, its rails clicking and clanking with a familiarity that will soon lull me to sleep. We’re rushing through the Swiss countryside, where I’ve been working this past week, and the Alps are a thick blur in the darkness. In a few hours, we’ll cross the border and make our way across the tiny, key-shaped country of Austria. Then in the early morning, we’ll reach Vienna, the place that I’ve been missing.

Below me in the lower bunk, my 10-year-old daughter is fast asleep, snug and content in the miniscule cocoon that is her bed for the night. I’m eager to share this adventure with her, to show her a part of myself that she may not know.

With air travel so cheap in Europe now, we could have flown to the Austrian capital for the same cost. But it only seemed right to travel to Austria by rail. After all, this is how I first came to know the former imperial city, when I was just another American kid schlepping a backpack through the train stations of Europe.

It’s funny how one decision can make such a difference, how a country I had barely even heard of could alter the path of my life.

I had planned to study abroad in Spain, where I have relatives and could understand a bit of the language. But then a friend dragged me on a two-week trip through Europe, and I came face-to-face with Vienna and a boy named Richard. I was instantly infatuated with both of them.

So Spain was forgotten, and I landed in Austria six months later at age 20 with three suitcases and two months of German study under my belt. I was to attend an American university in the Austrian capital, but it was the culture here that intrigued me.

Vienna is known as the city of music and for its famous coffeehouse culture. Many visitors, however, forget the town’s royal past. Yet, it’s from this unique viewpoint that this city of two million is best understood. For nearly 640 years, Vienna served as the heart of the mighty Austro-Hungarian Empire. The ruling family, the Habsburgs, stretched the fingers of their rule from Austria to Hungary, and even into what is now the Czech Republic. The royal family built beautiful palaces; ordered court composers (like Mozart) to write dramatic music; and ate the royal pastries that were invented just for them.

When the empire fell after World War I, the remnants of this imperial heritage remained. It lives on in the regal air of Vienna’s citizens, the haughty atmosphere in many cafés and restaurants and the highly-regarded arts and cultural scene.

World War II also left its mark on the city. The wounds still run deep from those shameful times, but many decades have passed, bringing new understanding and knowledge. After WWII, Europe was divided up between the Soviets and the West. While Czechoslovakia, Hungary and even parts of Germany were pulled into the Eastern Bloc, Austria was allowed to be “neutral,” a fragile outpost of Western thought walking gingerly at the doorstep of communism.

That is the Austria I met when I arrived in 1987. I have a photo at home from that first week in Vienna. In it, I am smiling, wide-eyed and naïve, open to whatever the city sends my way. And in the background, in the gray skies and the busy sidewalks of Mariahilfestrasse, Vienna stands wary, caught between East and West.

There is a Hungarian Lada driving past in a blur, a microwave strapped to the roof, rushing back across the border which may or may not be open tomorrow.

In the right hand corner of the photo, there is a weary old woman with a cane, wearing a coat of green Austrian wool, moving slowly across the cobblestone. And there in the corner, way off to the side, is a group of teens, not quite sure of their place in this city or even the world, but enjoying a smoke all the same.

We are all in transition in the photo, but we just don’t know it.

Vienna’s angst at being pulled between East and West was soon to find relief. That year marked the beginning of the end for the Eastern Bloc. The Hungarian fence would soon come down, and two years later, the Berlin Wall would fall. Europe was on a road of change, and Austria would soon be swept up in the current.

As for me, I was about to begin the journey that every foreigner feels when they move to a new country. At first, everything about Vienna delighted me — the quaint, narrow streets that made me feel as if I were walking into another century; the city’s distinct aroma of humid air, ancient buildings, fresh bread, cigar smoke and coffee — all mixed up together; the slow pace of life that allowed me to savor one glass of wine all afternoon in a restaurant; the tiny grocery stores with aisles that were only two people wide; the reserved Austrians who greeted each other politely when they arrived and left; and the aloof waiters who served me with flair and style.

It was all new and fascinating and amazingly wonderful. I wrote long letters home to my parents detailing each delightful discovery.

But the letters began to change as the city’s newness began to wear on my resolve. Used to open faces and quick smiles, I began to long for friendly stranger faces; the constant cigarette smoke made me gag; the narrow alleyways seemed confining and I longed for open spaces; Viennese pretensions got on my nerves; the tiny groceries didn’t carry enough products; and oh, the language struggles! The short German course I had taken was useless. The Viennese spoke a different dialect and I couldn’t understand a darn word they said.

All these feelings, I learned later, were a part of culture shock, the second phase that many foreigners go through. It was as if I were standing outside of Vienna, my nose pressed against the glass, watching those inside and wanting to come in, but not knowing how.

As is often the case when one has a problem, help came to me from a friend — several of them, in fact.

Richard, the handsome young man who had drawn me to the city, turned out to be only a friend, but a good friend indeed. He showed me his favorite haunts, and drilled me on my Austrian German, unrelenting when I couldn’t roll the Viennese letter “L” properly.

Still other friends came to light slowly. Compared to the American culture I grew up in, Austrians are quiet people, polite but often wary of strangers. You come to know them gently, one step at a time. But as one of my friends told me: “Once you have an Austrian friend, you have a friend for life.”

My new Austrian friends, it turns out, were the real treasure of Vienna. One of them was 15 years my elder; others years younger. But age never stops kindred souls from understanding each other. My friends welcomed me into their homes and lives. And through their eyes, I came to understand this city in her own way.

Vienna, I came to see, is a grand old lady with a reserved spirit and genteel manners. She will never jump into your face with welcome, but beckon quietly, gracious and waiting.

For example, to an outsider Viennese waiters may appear snooty and aloof. Sometimes this is the case, but often, it’s an air of pride and refinement. Dignity can be found in small things, such as serving a cup of coffee on a silver tray with spoon and sugar set perfectly to the side, while addressing your customer as gnädige Frau(gracious lady).

It was just one of the lessons this city had to teach me.

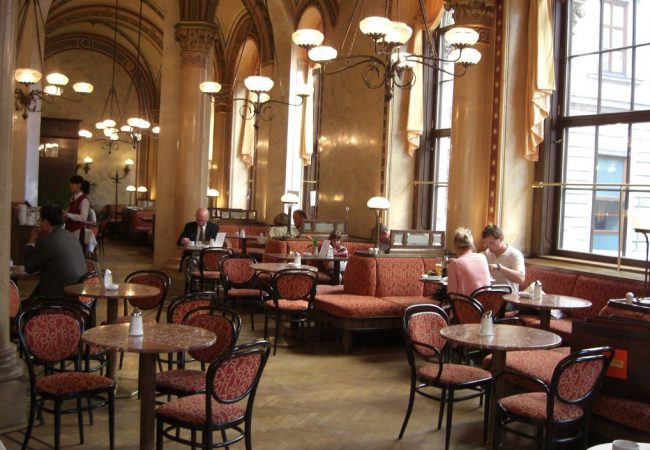

When I arrived in Vienna, I didn’t like coffee, wine, waltzing, classical music or political discussions. Yet one by one, these bastions of Austrian culture became a norm in my life. I spent long leisurely afternoons in my favorite cafés, lingering over a Wiener mélange (a cross between a cappuccino and latte) and a thick piece of chocolate Sacher torte, discussing politics and the meaning of life with friends.

In the rooms of a former palace, I learned to waltz in a long blue gown to the music of Strauss, confident in the arms of my partner.

Warm summer evenings were spent drinking g’spritzte (white wine and mineral water) at Mayer am Pfarrplatz, our favorite wine garden in the hills of Vienna. And as the months wore on, I began to tolerate — then actually enjoy — classical music.

How could I not?

My university was right across from the music conservatory, and each school kept their windows open. While I studied international relations with professors from the United Nations, I heard hour after hour of classical music. Even the street musicians play Mozart and Beethoven in Vienna. This is, after all, the city of music.

Most of all, I found a new perspective in Austria. The world is much bigger than the neighborhood where you live, the country you were born in. And when you live in a place wedged between two opposing powers, this becomes even more obvious.

When I returned to America two years later, I was a different person. I had come of age in the Austrian capital, and though still a foreigner, Vienna had become a part of me.

But years have passed since then, and as the train nears the station, I become a bit nervous. Will Vienna have changed as much as I have? Austria is now part of the European Union. The schilling has been replaced by the Euro; it is a whole new economy.

But I needn’t have worried. My Viennese friend, Nicole, is there to greet us at the station. I’m thrilled to find that the city still feels like home, no matter how long I’ve been away. It smells the same and the sounds haven’t changed. The streetcars have a fresh coat of paint and there are new stores along the streets, but I see the same faces and mannerisms, the culture that has stood here for centuries.

And yet, there is something different.

Vienna seems brighter, newer, pulsating with life. Though she has added years to her age, the city looks younger and wealthier. (If only that applied to me!)

The EU looks good on Vienna. There seem to be more products, better prices, better service. New trendy restaurants have popped up all over town; chic boutiques and shops line the avenues. Youth is everywhere — hip colors, bold music and the latest fashion — yet all done with that typical Austrian sense of style.

I see that vibrant pulse best on the Mariahilfestrasse, a well-known shopping street that had once been filled with second-rate stores and tired restaurants. It had been one of the more affordable shopping areas in the city, and I had spent many hours there as a student.

But it looks like a whole new neighborhood now. From the balcony of our elegant suite at the chic Hotel Das Tyrol, my daughter and I watch the street below. The sidewalks are filled with shoppers loaded down with bags from Swedish clothiers, Italian shoe shops and French designers — companies from all over Europe. It’s a whole new experience.

We spend the week with friends, visiting my favorite haunts, hiking in the Vienna Woods, having mélange at Café Central and shopping in the First District. I show my daughter where I used to live and I tell her stories of my time here. We visit the new MuseumsQuartier, where she plays at the children’s museum and practices her Viennese words, sounds she has heard since birth, though often in my American-accented tongue.

We marvel over the art at the Liechtenstein Museum and get sick on the rides at the Prater amusement park. And, all the time, we are with friends, the same friends who came to my rescue years ago.

On our last night in Wien, my friend Torsten takes me to Do&Co, a fashionable restaurant on the top of Haas Haus across from St. Stephen’s Cathedral in the heart of Vienna. The summer air is warm, so we sit outside, the light from the church drifting across St. Stephen’s Square below. I can see clear across the rooftops of Vienna, and below us, the city moves like tiny ants at our feet.

“So much in Vienna has changed,” I muse, “and yet, it still seems the same, don’t you think?”

Torsten, who is in mid-bite, simply nods at my contradictory statement. He knows what I mean, for Vienna is a city of contradictions. We spend the evening looking out over the Austrian capital, marveling over the wonders and pitfalls of the EU and the difference the years can make, not only in a country but in our own lives.

All the while, our waitress has been dashing about, serving table after table, but basically ignoring us. Finally, Torsten beckons for another coffee. The woman nods, barely acknowledging our existence. Yet minutes later, a coffee appears with elegant presentation. Then before we can thank her, the waitress is gone again. And then I know for sure that I’m back in Vienna.

If You Go

Austrian Tourist Office

www.austria.info

Vienna Tourism

www.vienna.info

Rail Europe

www.raileurope.com

Read More: Road Trip Through Austria

- Life of a Champion: Exploring the Muhammad Ali Center in Louisville - April 19, 2024

- What It’s Like to Live as an Expat: Lake Chapala, Mexico - April 18, 2024

- Top 5 Spots for Stargazing in North Carolina - April 17, 2024

Many thanks to Ms. Graber for the beautifully written memory of her past Vienna and the current city. I must visit it now.