“This place has the feeling of power,” says Mark Eddowes, a New Zealand archaeologist, at a large rectangular terrace enclosed by low stone walls on a steep wooded hillside. We are visiting the lovely tropical island of Moorea in French Polynesia.

Eddowes has been excavating and restoring ancient sites like these, called marae, for many years. They were open-air temples that honored gods and ancestors, where chiefs and priests once presided over rites intended to ensure such things as a good harvest or a successful military campaign. These involved the sacrifice of valued animals and often humans as well.

Our small group has joined a hike with Eddowes to inspect and understand several of these marae. One, associated with the god of archery, features a platform from which arrows were shot. Success in archery was a way of demonstrating mana, or power.

One family marae contained the jaw bones of defeated enemies. Another was built to commemorate the chieftainship of a man who had usurped the position of his rival. All are vestiges of a dynamic but brutal society that dominated the South Pacific for centuries. That world disappeared rapidly with the arrival of Western explorers, Christian missionaries, and the epidemics that came in their wake, which decimated the local populations and had a catastrophic impact on the culture.

French Polynesia Cruise

My wife and I are taking a week-long cruise on board the Paul Gauguin, sailing westward from Tahiti through the Society Islands. The ship is both luxurious and intimate, carrying only 332 passengers in spacious cabins. We sail to some of the Pacific’s most fabled islands, all of them mountainous, lushly forested, and encircled by protective fringing reefs. The warm, sheltered, turquoise lagoons inside those reefs are perfect for kayaking and other water sports. At each island, the ship offers shore excursions that afford insight into the region’s rich human and natural domain, both traditional and contemporary.

Huahine

At Huahine, the tides swirl in and out through a narrow channel. In ancient times, people built stone walls in the shallows, which funneled the lagoon fishes into small enclosures, where they were easily netted.

The fish traps had fallen into disuse until Hawaiian archaeologist Yosihiko Sinoto restored them in the 1970s. As we watch, local men reap a bountiful harvest. Our guide tells us that one of the men recently lost his job at a resort. He may be catching fish to sell, but more likely he needs the fish to feed his family.

At Tahaa, we snorkel through a “garden” of splendid pastel corals, drifting with the current. We visit a farm that raises black pearls and another where vanilla beans are grown. Along with tourism, these provide modest employment. But islanders are largely self-sufficient. They fish, raise pigs and chickens, grow taro and yams, and are surrounded by tropical fruit trees.

Bora Bora

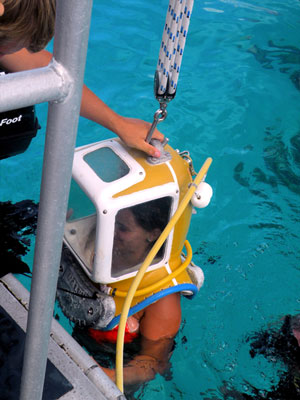

Some of the excursions are more adventurous. At Bora Bora, we don helmets with air hoses and descend to walk along the sandy sea floor. Feeding bread to colorful fishes that swirl around our faces, we stroke the soft skin of sting rays as they swoop past and kneel for close views of soft living corals. Tiny fishes flit in and out of the undulating coral fingers.

One of the ship’s on-board lecturers is American biologist Michael Poole, a specialist on whales and dolphins. He has long studied Moorea’s spinner dolphins, which number 160, and found them to be a population distinct from those of Tahiti, which is only 10 miles away.

Raiatea

The traditional language has fared well in French Polynesia. On Raiatea, an island that we fly to following our cruise, we attend a Protestant church service. The hymn books are entirely in Tahitian; not a word of French is spoken in the sermon. Yet French influence is evident elsewhere. Along rural roads, people wait for the daily van that delivers long, thin, freshly baked baguettes. There are signs of the heavy subsidies provided by the French state, such as tidy, perfectly paved roads and new cars. Each village has its gendarmerie, clinic, fully stocked grocery stores and healthy, well-fed people.

Taputapuatea

The most vivid and lasting impression comes from the vast seaside marae complex of Taputapuatea, on Raiatea. This was the spiritual center of ancient Polynesia, home to the cult of Oro, the god of war and fertility. According to legend, it is also the place from which the greatest canoe voyages of exploration and colonization departed 800 to 1000 years ago. Navigating only by the stars, prevailing swells and watching the flight of birds, these large twin-hulled craft discovered both Hawaii far to the north, and New Zealand in the distant southwest.

The so-called warrior’s marae is dominated by a tall stone in the center. Only men who measured up, about six foot six, were deemed acceptable for combat. The larger main marae features a long wall of flat stones about 13 feet high and carved totem-like wooden planks representing animal or human figures.

Archaeologists have found human bones under some structures, likely the remains of sacrifices to that fierce god. The story goes that Oro was frequently copulating with the goddess of the land and was weakened thereby, so he needed to be fed with male vibrancy. Warriors were sent out each year to snatch a number of unlucky young men. Pigs and dogs were also offered as sacrifices.

War and conquest were the very essence of life in the Society Islands for centuries. And then, in 1817, the missionaries arrived. Islanders rapidly embraced Christianity, and the marae were abandoned.

But Taputapuatea continues to be revered as a shrine by many Polynesians, especially those who have re-kindled the tradition of distant canoe voyaging in recent decades by building modern “replica” canoes and learning to navigate them without instruments.

In the mid-1990s, canoes from across the Pacific rendezvoused here for ceremonies celebrating the unity of the Polynesian people, language and culture. Along the high wall of stones are many more recent offerings: flowers, shell necklaces, pottery and stones brought from distant archipelagos.

Finding a quiet spot to sit, gazing out to sea, I find myself torn. On the one hand, I realize that this marae, and others like it, was built by war chiefs commanding the forced labor of hapless underlings in an oppressive and violent social system. It became the focal point of dark and terrible deeds.

On the other hand, the vast and unmapped reaches of the Pacific were conquered by Polynesian sailors who set out from here, guided mainly by the stars, trusting only to their hand-carved wooden canoes. Surely, this ranks among the most daring and heroic accomplishments in all of human history.

Author bio: Tom Koppel is a veteran Canadian journalist, author and travel writer whose latest book, Mystery Islands: Discovering the Ancient Pacific, can be obtained by writing to [email protected]

- Cruising with Discovery Princess on the Mexican Riviera - March 30, 2024

- La Paz, Mexico: Pearl on the Sea of Cortez - February 26, 2024

- 9 Places to Experience Amazing Sea Life Up Close - January 26, 2024